Short Book Reviews: Volume VIII

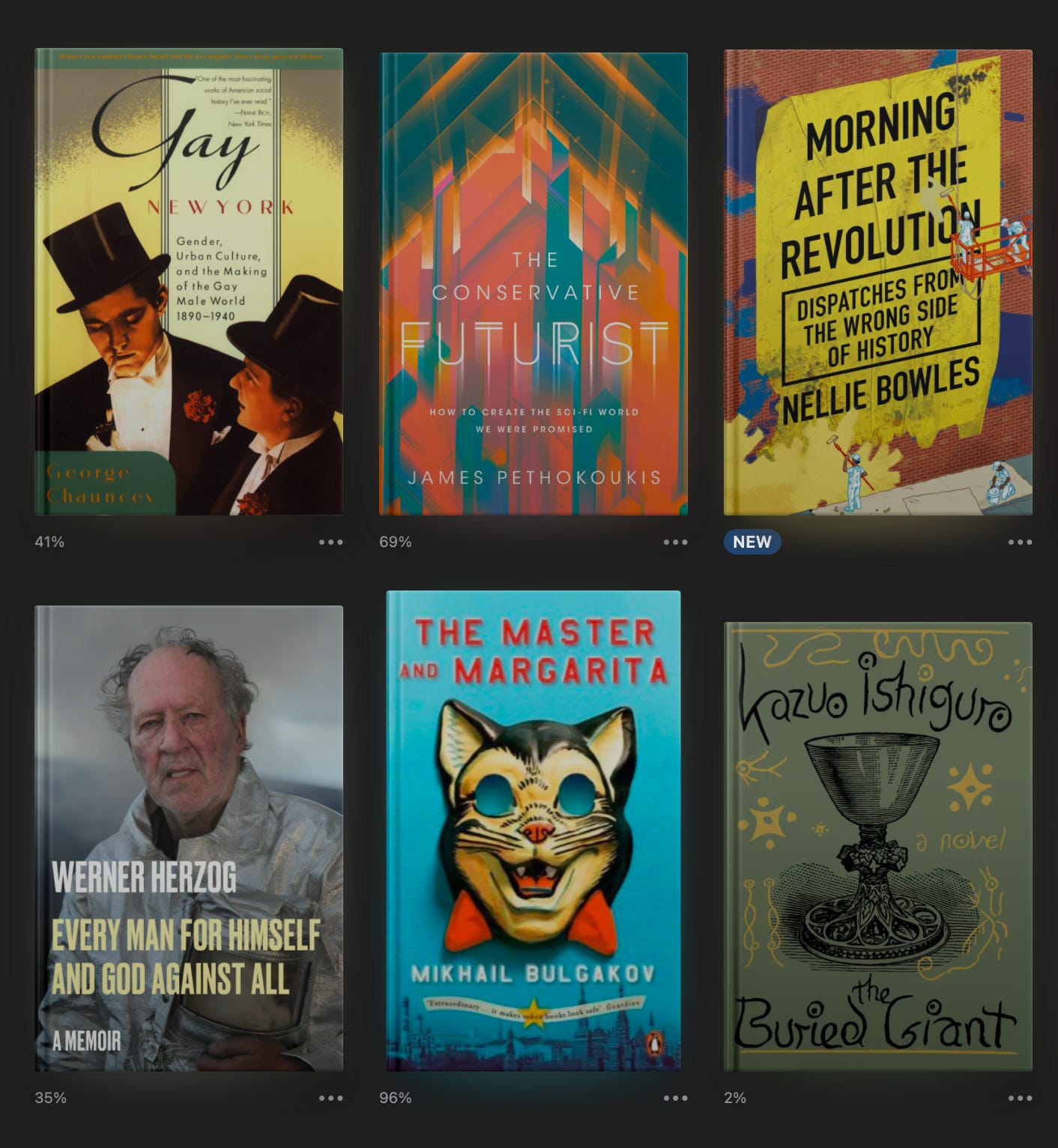

Gay subculture, conservative futurism, wokeism run amok, Werner Herzog at his herzogiest, the Holocaust, Russian lit, Kazuo Ishiguro, weird Canadians, Inspector Morse, and D&D.

Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture, and the Making of the Gay Male World, 1890-1940 by: George Chauncey

The Conservative Futurist: How to Create the Sci-Fi World We Were Promised by: James Pethokoukis

Morning After the Revolution: Dispatches from the Wrong Side of History by: Nellie Bowles

Every Man for Himself and God Against All: A Memoir by: Werner Herzog

The Complete Maus: A Survivor's Tale by: Art Spiegelman

The Master and Margarita by: Mikhail Bulgakov

The Buried Giant: A Novel by: Kazuo Ishiguro

Naked Defiance: A Comedy of Menace by: Patrik Sampler

The Riddle of the Third Mile (Inspector Morse #6) by: Colin Dexter

Dungeons & Dragons 2024 Player's Handbook (D&D Core Rulebook) Lead Designer: Jeremy Crawford

I’ve finally dug out after a very busy summer, and sworn to never again have a summer that’s quite so crazy. (Whether this oath will stick is another matter. It’s always interesting how I’m very good at keeping promises to other people, but mediocre at promises I make to myself.) Beyond that, to the extent that anyone can quantify something as amorphous as mojo, I think mine has returned! As part of that return, here's my plan moving forward.

I’m going to start putting some of my book reviews in their own episodes. As someone pointed out, many of my book reviews are not particularly short (contra the title of this episode). When you combine that with the recent attention received by my review of Bad Therapy—which was easy to reference because it was all by itself—splitting off longer reviews seems like a way of better harnessing potential interest.

As a result of the foregoing I’m hoping that I can get back to (mostly) publishing every week. In fact, based on another change I’m making, I might even be able to do more than that.

It’s not going to be all book reviews. I have lots of other pent-up ideas. You’ll also be hearing a lot about forecasting, because I plan to write a book about it. This is territory I’ve covered extensively in the past. So ideally it will be reasonably straightforward to put together a book.

Of course all of this is subject to von Moltke the Elder’s famous observation, “No plan survives contact with the enemy.” But it’s still important to have a plan regardless.1

For those that have stuck with me while I did whatever it was I was doing over the last year or so, I’m very appreciative, and for new readers, the best is yet to come (probably).

Non-Fiction Reviews

Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture, and the Making of the Gay Male World, 1890-1940

By: George Chauncey

Published: 1994

512 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

How male homosexuality was conducted and expressed in pre-war New York.

What's the author's angle?

Chauncey is a major gay rights advocate, and has been particularly prolific as an expert witness in gay rights cases. From Wikipedia:

Chauncey has testified as an expert witness in over thirty major gay rights cases, and was the organizer and lead author of the Historians' Amicus Brief in Lawrence v. Texas (2003), which weighed heavily in the Supreme Court's landmark decision overturning the nation's remaining sodomy laws.

Who should read this book?

Most people’s understanding of gay history begins after World War II. The repression of the 50s, the gradual opening up during the 60s, Stonewall, the thawing over the decades until eventually same sex marriage was legalized and gays ended up with all the rights held by heterosexuals. If you imagine from this that the prewar period was like the 50s only even more tyrannical, this is the book for you.

Specific thoughts: Wow! There was a huge variety of homosexuality in early 1900’s New York

I grew up in rural Utah during the presidency of Ronald Reagen. I was in the Young Republicans when I was a senior in high school, and ended up in a campaign video for George H. W. Bush. Let’s just say that’s a long way from the gay scene in pre-war New York. Given this I bring significant, mostly unconscious, biases towards this book. I experienced an under-sampling of libertine homosexuality in my youth. I dare say that this book offers up a huge over-sampling, but given the aforementioned biases I’m not the best person to opine on the topic.

I do think I can say a few things however. First, in the pre-war period, homosexuals were not some tiny, hidden population, hounded into near extinction. At least not in New York. I assume that elsewhere, particularly in rural America, things were different, but in New York the gay scene was huge and quite a bit more aboveboard than I had imagined.

This does not mean that it was mainstream. It was something which was kept semi-secret. There seems to have been something of a tacit détente between the homosexual community and the police. The community would keep to certain areas and establishments, and the cops would pick up the occasional individual. But, there was never a huge crackdown, though things were obvious enough that there could have been.

Because it was not mainstream it was not necessary to fit it into a box. In the run-up to the legalization of gay marriage, one of the major talking points was that gays were just like everyone else, and they just wanted to get married, in the same fashion that hetrosexual couples did. This is not the impression one gets from reading this book. Chauncey describes all manner of behavior, and different distinctions and gradations of homosexuality. The biggest one (trying to put it delicately): having certain things done for you, did not make you gay, but having certain things done to you did.

The point I’m trying to build to: when something is illegal, but widespread, one can see all manner of behavioral variations. If it’s already illegal why not engage in your preferred “fetish”? Why not do whatever you feel like? But for something to become mainstream you have to file off the rough edges to fit it into the “mainstream box”. Or at least that’s my theory. Regardless, it seems clear that Chauncey regrets this loss of variety.

The Conservative Futurist: How to Create the Sci-Fi World We Were Promised

Published: 2023

336 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

How conservative free-market principles are the best way to bring about a future of maximum happiness and material abundance.

What's the author's angle?

Pethokoukis is a fellow at the American Enterprise Institute. According to Wikipedia AEI favors private enterprise, limited government, and democratic capitalism. All of which is to say Pethokoukis is an ideological pundit, and this book is ideological punditry.

Who should read this book?

People who don’t want to read the longer (but superior) Where is My Flying Car? by J. Storrs Hall. (See my discussion of that book here.)

Specific thoughts: We need a cultural conservative’s vision of the future.

I already know the economic conservative’s vision of the future—the free-market, technology-will-solve-all-our-problems, pro-business vision. It’s the operating ideology for numerous groups and individuals, from Silicon Valley all the way through to Matt Yglesias (on most days). What is vastly under-defined is a strong cultural conservative vision for the future, that is also actually futuristic (not retrograde). We’re getting something of that in the discussion of fertility decline, but it’s still a largely unexplored space. I had hoped that this book would do some of this exploration, but it did not. Instead it was basically the same thing Storr was saying in Where is My Flying Car? and the same thing Marc Andreessen was saying in his Techno-Optimist Manifesto. This is fine, but neither novel, nor particularly interesting once you’re hearing it for the fifth or sixth time.

Morning After the Revolution: Dispatches from the Wrong Side of History

By: Nellie Bowles

Published: 2024

272 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

Peak wokeness from the perspective of someone who started as a NYT reporter and ended up mostly canceled.

What's the author's angle?

Bowles is not a fan of the events she’s describing and the book’s basic purpose is to point out how ridiculous it all was. In other words this is not a steel-manning of wokeness, but I don’t think it’s fair to call it a straw-man either.

Who should read this book?

If you have forgotten how crazy things like CHAZ and abolish the police and antiracism got. Or if you want to revel in the ridiculousness, this is the book for you.

Specific thoughts: What happened? Were there consequences?

Reading this felt similar to reading Bad Blood, the inside story of the rise and fall of Theranos. There are points in both of these books where your jaw drops at the sheer insanity of the events being described; when you wonder how on earth did someone ever come to the conclusion that X was a good idea?

For Theranos the big questions are, how did the culture of Silicon Valley, the drive for innovation, the fear of missing out, and the greed of VCs create such a huge corporate facade?

For wokeness the big questions are how did elite liberal culture, the drive for justice, the fear of the status quo and the greed of social justice activists result in one of the largest episodes of widespread insanity the country has ever witnessed?

Along with these similarities there is one big difference: the outcome. Theranos is no more and Elizabeth Holmes is in jail. Everyone (or nearly everyone) agrees that the revolutionary technology Theranos claimed to have was an illusion. On the other hand, wokeness is still with us. Robin DiAngelo is still giving keynote speeches and many people believe the social justice revolution is just getting started.

That said, clearly things aren’t as crazy as they were in 2020, and perhaps it’s just going to take longer before we can truly acknowledge how insane ideas like “defund the police” really were. Certainly Harris and Democrats in general seem much more law and order at the moment. But I think there’s a lot of lingering madness which still remains to be rooted out. This book is valuable as an accounting of how much madness there was.

Every Man for Himself and God Against All: A Memoir

By: Werner Herzog

Published: 2023

368 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

An autobiography of Werner Herzog, from his early childhood in WWII and impoverished post-war Germany to the present day.

What's the author's angle?

Herzog definitely has a very unique point of view, and you get the impression that he hasn’t modified it at all for this book. He couldn’t care less what you think of him.

Who should read this book?

If you have any affection at all for Herzog, or unique individuals in general, I think you’ll enjoy this book. And I wouldn’t read it, I would listen to it. Herzog does the narration and it’s fantastic.

Specific thoughts: Herzog doesn’t pull any punches

Perhaps you know someone who seemingly has no end of amazing stories, to the point where you start to wonder if perhaps he’s a pathological liar? But then as you get to know them better you realize they’re all true? That’s Herzog.

He’s been shot on camera.

He threatened to murder one of the actors on a film he was directing, and he meant it.

He “promoted” (i.e. stole) his first film camera.

He was trapped on top of a mountain during a monstrous blizzard for 55 hours.

The list goes on and on.

After doing all of that, he doesn’t care what people think about him, or his opinions. He’s going to give it to you straight. Which is why I love this quote from the book:

I have a deep aversion to too much introspection, to navel-gazing.

I’d rather die than go to an analyst, because it’s my view that something fundamentally wrong happens there. If you harshly light every last corner of a house, the house will be uninhabitable. It’s like that with your soul; if you light it up, shadows and darkness and all, people will become “uninhabitable.” I am convinced that it’s psychoanalysis—along with quite a few other mistakes—that has made the twentieth century so terrible. As far as I’m concerned, the twentieth century, in its entirety, was a mistake.

As big of a doomer as I am, I don’t think the entirety of the 20th century was a mistake, but I would agree that it is far more of a mixed bag than most people think.

The Complete Maus: A Survivor's Tale

By: Art Spiegelman

Originally Published: 1980–1991

296 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

A graphic novel recounting the experiences of the author’s Jewish father during World War II. From his time as a young man in Poland through his stay in the concentration camps and, eventually, the end of the war.

Who should read this book?

I can’t think of many reasons why someone wouldn’t read this book. Certainly everyone should have a decent familiarity with the holocaust, and this book is one of the most pleasant ways to achieve familiarity with a very unpleasant topic. (I found it easier to read than Schindler's List was to watch, even if it took longer.)

Specific thoughts: A unique way to present things

This book has added several presentational layers all of which serve to create some distance between the reader and the story. Which is probably necessary, since it’s such an awful story. The first and most obvious is the fact that it’s a graphic novel. Secondly, as the title alludes to. Rather than being depicted as humans the Jews are depicted as anthropomorphic mice and the Germans are depicted similarly as cats. Finally there is the outside story of Speigelman’s father in the present day relating his experiences of the war. The present day story includes its own plots and twists. (These are mostly related to the rocky relationship between the father and his second wife.)

Taken together, these artifices make it a very interesting book, even before we get to the story. But then the story itself, how a Jew living in Poland at the beginning of the war, managed to survive to the other side, is one of the most enthralling you’ll ever read.

Fiction Reviews

The Master and Margarita

By: Mikhail Bulgakov

Published: 1967

448 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

The devil visits Soviet Moscow and raises havoc. Also there’s a story about Pontius Pilate.

Who should read this book?

This book feels very Russian to me, if that means anything to you. I very much enjoyed some sections and was bored by others. It’s heavily satirical, and widely considered to be a modern classic. If any of that triggers some degree of yearning in you, you’ll probably enjoy the book.

Specific thoughts: The Devil in literature

Wikipedia describes the novel thusly:

The story concerns a visit by the devil and his entourage to the officially atheistic Soviet Union. The devil, manifested as one Professor Woland, challenges the Soviet citizens' beliefs towards religion and condemns their behavior throughout the book. The Master and Margarita combines supernatural elements with satirical dark comedy and Christian philosophy, defying categorization within a single genre. It exhibits autobiographical elements, but is also dominated by many aspects of fiction. Many critics consider it to be one of the best novels of the 20th century, as well as the foremost of Soviet satires.

As I attempt to review it, the “defying categorization” seems very pertinent, but I do wonder if it belongs to that small genre of works that feature visits from “the” or a devil. Like Faust, The Devil and Daniel Webster, or even works like The Screwtape Letters and Paradise Lost. In these books the devil often steals the show, and is always a character of great interest. Why should that be? Why is he not a figure of abhorrence and disgust? I think this novel provides a good example why this should be.

The devil is great at puncturing the pretensions of the supposedly wise and mighty. He’s fantastic at taking people down a peg. This proves particularly easy to do in the “officially atheistic Soviet Union”.

We also like to see people get what they deserve, another thing at which the devil excels. We might entertain a fantasy that the person loudly talking on his cell phone and ignoring the comfort of those around him, will get run down by a car while talking on his cell phone and ignoring traffic. But for us to arrange that would be a great crime. However, if the devil does it, it seems not only just, but humorous.

There are points later in the book where the Devil acts more like the Faerie King than the avatar of fitting punishment (I’m thinking in particular of the Satan’s Ball scene). These are the parts I found boring.

As one final thought, I can already tell that this will be one of those novels where the longer I sit with it, the more I’ll appreciate it.

The Buried Giant: A Novel

By: Kazuo Ishiguro

Published: 2015

317 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

The journey of an elderly couple (Axl and Beatrice) through Ishiguro’s version of post-Arthurian England. The primary feature of the setting is a memory-destroying mist which lays over the land. The couple decide to act on the dim memories of their son by journeying to visit him, before those memories are entirely lost. Along the way they encounter a warrior, a cursed boy, and an aged Knight of the Round Table.

Who should read this book?

Those who would find a story about aging and forgetting to be cathartic. I read it because Freddie deBoer selected it for his book club.

Specific thoughts: The value of forgetting

The book starts on a melancholy note. Axl and Beatrice are sympathetic figures, and we’re made to experience their sorrows and mourn for what they have lost. Their forgetting is painful. But as the book goes on there are hints that some things are better forgotten. Some pains are better left buried. The difference between what should be remembered and what shouldn’t forms the major theme of the book. But balancing on that theme is the question of how forgetting plays into having a healthy relationship. If Ishiguro is to be believed most relationships would not work at all if there wasn’t some forgetting as the years pass.

Naked Defiance: A Comedy of Menace

By: Patrik Sampler

Published: 2023

184 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

The strange goings on within a radical collective of street artists, all culminating in a tragic end.

Who should read this book?

I don’t know. I’m not sure if this book fits into some style I’m unfamiliar with, and fans of that style would appreciate it. Absent that, perhaps it’s not the sort of thing anyone will love, though it’s not especially bad, just not exceptional on any axis.

Specific thoughts: Weird, but not weird enough?

Naked Defiance is a group that meets in the nude, so that’s where the “naked” part comes from. The “defiance” is a little bit harder to pin down. They come up with missions where they’re supposed to expose the fetishism of modern consumerism, but the missions mostly end up being strange ways of walking around. The main character, Florian, seems to be going through something, but it’s never really clear what. And he reconnects with a girl from his past, but that doesn’t really develop very much either. Eventually it seems like it’s going to be a story about the way progressive groups often collapse into infighting, but it’s too little too late. I liked the characters, and there are some interesting ideas, but they never really get fleshed out.

The Riddle of the Third Mile (Inspector Morse #6)

By: Colin Dexter

Published: 1983

224 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

A dismembered corpse is discovered in the Oxford canal, and Inspector Morse must figure out who it belongs to, and who did the dismembering, all while remembering his own, unsuccessful stint, at Oxford.

Who should read this book?

In this case I may not be qualified to judge. I don’t have a lot of experience with murder mysteries, but from the experience I do have, this one seemed subpar. Though I gather it’s one of the weaker entries in the Inspector Morse series.

Specific thoughts: So why this book?

You may find it odd that I started with the sixth book in the series. I really have tried to be more systematic in how I read, but someone mentioned this book in passing. I have long had the vague feeling I should read more murder mysteries (my wife and daughter love the genre) and before I really got around to questioning why I was reading the sixth book and not the first book I was halfway done. (In my mind this all happened in about 30 minutes, in reality it was about a week, but when you’re my age a week can feel like it went by in 30 minutes.)

As mentioned, I’ve heard it’s one of the weaker entries in the series (though on Goodreads it’s 3.85 and the first book is 3.83…) so I don’t know if it’s fair to judge the entire series by it, but I found it enormously convoluted, and entirely unbelievable. That said, I am not a connoisseur of this genre, and beyond that I’m a bear of very little brain, so perhaps it’s just me. I did like Morse, and his sidekick Lewis.

RPG Review

Dungeons & Dragons 2024 Player's Handbook (D&D Core Rulebook)

Lead Designer: Jeremy Crawford

Published: 2024

384 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

A significant update to the Dungeon and Dragons Fifth Edition rules. Character classes appear to have received the biggest update, spells appear mostly unchanged, and races (now called species) and backgrounds fall somewhere in the middle.

Who should read this book?

This is not the sort of book you read cover to cover—though I came pretty close. This is the sort of book you acquire as a reference. If you’re going to play this new version you should definitely pick it up. If you’re just curious about changes I would buy an electronic copy on DNDBeyond.com. Or, even better, I believe they allow you to generate characters for free, doing that would probably give you most of the information you’re looking for.

Specific thoughts: Impressed by the crunch repelled by the art

As mentioned the character classes appear to have received the biggest reworking, and I liked just about all the changes. They are clearly more powerful than the previous 5E versions, which makes me interested to see how they balance that when it comes to monsters. The fact that they moved the initial stat boosts from races/species to backgrounds is also an improvement in my opinion. As a consequence of all this if I were planning on running a game of Dungeons and Dragons I would use this system.

However the art is pretty cringy, which I say knowing that art is pretty subjective. By saying it’s “cringe” I’m not saying that it’s not necessarily bad. I would even say that its “wokeness” (very broadly defined) has been overblown by those commenting on line. But… it definitely has a very specific aesthetic. I’ll try to explain:

When 4E was being introduced, they talked about most D&D settings being “points of light” settings—you have small enclaves of civilization that are surrounded by darkness, monsters, and looming death and destruction. I get the opposite feeling from the new art. I get the impression that the world of the new edition is a pastel wonderland, where people occasionally spend a weekend battling monsters in almost an amusement park fashion.

There’s one image which perfectly encapsulates what I mean. I would post it, but I’ve heard Wizards of the Coast has been draconian with Cease and Desist letters. So instead I’ll describe it. It’s a woman in a pastel dress with a purple pastel umbrella, she’s casting a spell with a wand, and the caption reads “A human Sorcerer chastises ghouls with the unpredictable energy of a Chromatic Orb.” Chastises??? Are they being impolite at her tea party? Did they get blood on her pretty dress? Did they forget to say please? Ghouls are ravening undead who paralyze the foolish and devour them while they yet live. You don’t chastise them, you hunt them through dark graveyards, and kill them in righteous holy anger all the while praying that they don't kill you first and force you to join them in their ravenings.

Speaking of ravenings… Oh I guess what I do is ravings, as in the “ravings of a madman”. If you want to hear me actually raving see the link at the top, for all of my ravings check out the podcast feed. Just search for “We Are Not Saved” in the podcast app of your choice.

A more complete and accurate translation is “No plan of operations reaches with any certainty beyond the first encounter with the enemy's main force.” To put it in the language of forecasting I’ll assign a 60% confidence level to my plans.

Regarding the devil always stealing the show, that often seems to be the case with villains in general. Everybody remembers Darth Vader, Frollo, Maleficent, etc. I recently finished the audiobook "The Insidious Dr. Fu-Manchu", the first in a pulp series NAMED after the villain. I suspect in addition to the points about the devil that you mentioned, there is also the attraction to the forbidden that villains represent. They get to ham it up, stick it to those asking for it, take what they want, and sometimes even be in charge for a while before being deposed. The comic Order of the Stick has a villain who is very aware of how the story needs for him to be defeated. But he counts his blessings, being content to live it up until he's deposed. He's not even worried about his reputation or legacy: "Audiences always think the villain is cooler than the hero is, anyway."

> What is vastly under-defined is a strong cultural conservative vision for the future, that is also actually futuristic (not retrograde).

This is interesting to me for two reasons. One is, I'm not exactly sure what you mean by "cultural conservative" and "not retrograde" in this case, and I would be interested to hear what you mean.

The other is that arguably my own writing is kind of "culturally conservative" for some definition of that term, and futuristic. I'm interested in the topic of the future of culture in general.