How Fast Is Technology Moving? Is That Even What We Should Be Measuring?

Perhaps it's not how fast technology moves, but where it's impact is felt? Also S-curves...

I.

I’ve always been amazed and fascinated by how quickly we went from the Wright Brothers inventing powered flight to landing men on the moon: a mere 66 years.

Imagine an 18 year old private, in 1909, attending the military trials of the Wright Flyer in Fort Myer, Virginia. Then imagine this same individual sitting in front of a TV watching the moon landing, 60 years later, when they were 78. It’s truly nothing short of miraculous to go from getting a few hundred feet off the ground to going 239,000 miles into space in less than a human lifetime. And not only going that far, but also escaping the gravity well, landing in an entirely hostile environment, and then returning.

We’re quickly approaching 60 years since the moon landing. In place of the dramatic progress experienced by the hypothetical person in the previous paragraph, our progress in this area over the last 60 years has been underwhelming. As an example of the kind of thing people expected, consider 2001: A Space Odyssey. Released in 1968, it was meant to be a relatively realistic depiction of what people expected out of the next 30 years: lunar bases, manned missions to Jupiter, and fully sentient AIs. Instead, we have yet to even return to the Moon.

The grubby realities of politics and money overwhelmed our more fantastic hopes and dreams. Certainly there were moments where we tried to take the next step. Consider the Concorde, the supersonic airliner in operation from 1976 to 2003—a nice run, but a temporary one. Here in 2025 our planes fly at about the same speed as they did in 1969.1 We’re still driving on the same interstates with, fundamentally, the same internal combustion engines as those in 1969. There have been lots of incremental improvements, but when you consider these depressing facts, there’s a case to be made that technological progress has slowed way down.

II.

Detractors of this argument will point at the computer, where there has been dramatic improvement over the last 60 years. Though clearly it’s been a different sort of progress than many people expected. One is reminded of Peter Thiel’s comment:

We wanted flying cars, instead we got 140 characters.

Nevertheless, there has been dramatic progress. In 1969, the entire computing power of most US states was less than the phone in your pocket. If we want to replicate the example from above we can imagine someone, say for instance my father, who was using punch cards to program mainframes in 1969, in order to do engineering calculations. Now, at the age of 76, he can just type his question into an LLM and get the answer to whatever question he might have. (Assuming no hallucinations.)2 This certainly seems like a similarly amazing amount of progress.

Nevertheless at first glance these two arcs don’t appear to have a lot in common.

On the one hand we have a giant leap that represents hacking our physical world. We developed the ability to travel farther and faster and, perhaps most consequentially, blow things up from a greater distance.

On the other hand the giant leap with computers is mostly virtual, starting with virtual ledgers and moving up to the creation of entire virtual worlds. Given these overt differences, can the first arc tell us much about the second arc?

III.

To begin with should we expect something analogous to the moonshot? Perhaps it’s recency bias, but the desperate scramble for better and better AI seems very similar to the giant effort required to put a man on the moon. Facilities are springing up. The best and the brightest are pulled in. There’s a frisson of excitement and anticipation among the public. Sure in the first case it was the government, and in this case it’s the private sector. But the parallels are nevertheless interesting.

So if we were trying to get to the moon in the first instance, where are we trying to get in the second instance? Many people would say artificial superintelligence. But I think that’s akin to science fiction writers imagining bases on Ganymede. The real analogy for the moonshot, the thing we’ve been striving for since the invention of the computers, is virtual people.3 Something that would pass the Turing test. We’ve done that, but I’m imagining another parallel.

Back then, everyone imagined that landing on the moon was just the first step to a glorious interplanetary future. These days people are imagining that the LLMs we currently have are mere months away from fully general artificial intelligence, and from there it’s just a few years at most to superintelligence. Obviously that’s possible, but there are signs that things may be leveling off. It looks like we might end up with smart, but somewhat unreliable virtual assistants—in a manner analogous to the way past science fiction writers imagined that we would colonize and eventually leave the solar system, but we only ended up getting to the moon. The reality of a technology may always end up falling short of our confident predictions.

If this should end up happening, we would have had two arcs of progress, built on entirely different foundations, but which ended up going at about the same speed. (i.e. around 60-70 years from beginning to moonshot.) So, perhaps, talking about technology slowing down is the wrong way to frame things. A better model is to view each arc of technology separately as something that goes very fast once the necessary engineering competence is in place, but the advancements eventually reach the limits of what can be done within that arc.

IV.

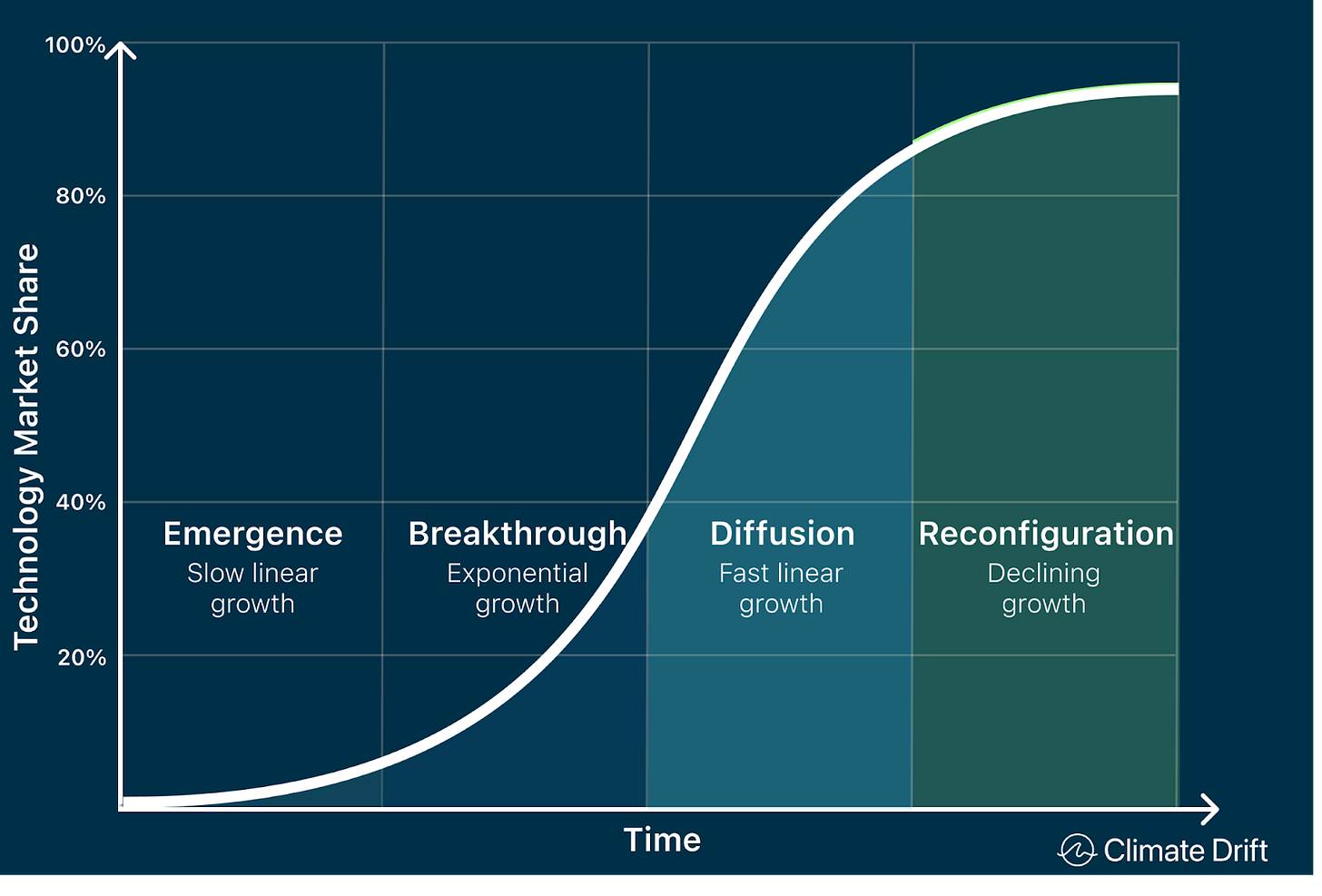

At this point I know a lot of you are saying, “How cute, he thinks he’s invented S-curves.”

I was too lazy to make my own S-curve graph so I borrowed this one from

Not really, the point I want to make is a subtler one. If we replace “speed of technological progress” with “identifying and categorizing S-curves” how does that change things? The original question is still an important one. “Is the rate of technological progress slowing down?” I don’t think changing the focus to S-curves necessarily answers that question, but I can think of several ways where this change of focus might lead to better, more illuminating questions.

1- There are a large number of people who are sure that the AI revolution is not an S-curve. Why is that? If every past technological advance could be plotted on such a curve, it would be surprising to find out that AI is the one exception. (And yes I’m aware of the intelligence explosion argument.)

2- Would we get a better view of the rate of technological progress by counting up the number of S-curves? Is such a categorization effort even possible? If we’re interested in the speed of technological progress at any given point in time would it be better to count up the simultaneous S-curves?

There were not very many in the 10th century. There were a lot in the 20th century. Somewhat in advance, but overlapping with the powered flight curve we had the automobile curve.4 And also the nuclear S-curve.5 Would it still be reasonable to say that technology went faster back then because we had a lot more S-curves going on in parallel during the 40s and 50s?

3- Do S-curves have a predictable duration? So far I’ve come up with a couple that both appear to be in the 65 year range, and I’m sure I could come up with several more. (Physics from Maxwell’s equations to Bohr/Heisenberg/Schrödinger quantum mechanics was just over 60 years.) Or is classification of S-curves in this fashion too susceptible to manipulation?

4- Are there different sizes of S-Curves? Major ones like computers and minor ones like reconfiguring transoceanic freight around the shipping container. Would creating that sort of classification system yield any useful results in terms of determining the rate of technological change?

5- If AI is the peak of the “computer” S-curve, what’s the next big S-curve? Genetics? Is the moonshot there immortality? Or like the actual moonshot, and (potentially) AI will we fall short of this lofty goal?6

6- Does the concept of a moonshot have a particular utility? Is it useful to identify the “moonshot” of a particular arc? Does every S-curve even have a moonshot?

7- Most S-curves have ultimately had some outcome in the physical world: increased crop yields, faster travel, bigger explosions, better health. The computer S-curve seems to have created an entirely new, virtual world. Is this an argument for the slowing of technology? Or an argument that we’ve reached an entirely different stage of advancement with previously unseen, and potentially terrifying, implications?

V.

I don’t have the time or the space to cover all seven of these points, nor do I necessarily have answers to all the questions I raised. So I’d just like to focus a bit on that last point. Is the computer S-curve with its virtual worlds, and potential virtual people different in some fundamental respect from previous S-curves. Will it turn out not to be an S-curve at all, but an exponential take-off as some boosters imagine? Or will it just move progress into a new unexplored realm with new potential blessings and horrors? Or is this silly?

Certainly people have had silly worries about new technologies before. The worry that people might suffocate on trains travelling over 30 mph, is a popular one, though it turns out to be apocryphal. Still there were worries of overstimulation, fatigue, and “railway shock”. And all of these worries turned out to have been wrong, or at least overblown. Transportation technology has mostly been a boon. There are a few negative second-order effects ranging from circadian disruption on the low end all the way up to easier worldwide transmission of plagues on the high end. But you’d have to be a serious luddite to argue that it hasn’t been a net benefit.7 Also I would argue that we have a pretty good handle on the negatives of transportation technology.

The same cannot be said for the negative effects which attend the virtual worlds we’re creating with computers. And as we close in on the “moonshot” phase of this technology they seem to be proliferating (AI’s effect on education, epistemology, and entertainment just to name a few.) And this is setting aside worries about the issue of artificial superintelligence killing us all. Even if we just focus on the virtual connections of social media, the virtual worlds of video games, and the virtual relationships of AI there is cause for significant concern.

In the past, one of the reasons why I was interested in the speed of technological progress is that I equated speed with impact. On a certain level it does make sense, the faster technology changes the harder it is to adapt to. But the computer S-curve, all by itself, is providing plenty of adaptation challenges.

The actual, literal moonshot was watched by millions, and as an inspiration event it was unchallenged. But if you only count the people whose day to day lives were fundamentally different, it only affected somewhere between 12 and 400,000. (Depending on whether you count just those who walked on the moon or everyone involved in the space program.) With even the larger number being only a small fraction of humanity. Even if we broaden things out to flying, only 11% of people worldwide fly in a given year. Whereas 68% have access to the internet, and the vast majority of them use it every day. This means all these people already have access to free versions of all the LLMs. The virtual moonshot is shaping up to be far more widely available than the literal one.

This is one of those posts where I was trying to work out things in my own mind, instead of pontificating from on high. I started by considering the speed of technological progress. On reflection, considering technology as a series of S-curves seemed to reflect things better than a single metric for speed. But once you start to split these curves out, I noticed that the computer/AI S-curve seemed to have some unique qualities. In the past we fed more people, or traveled to more places, or built better things, but all in the physical world. Now we have a virtual world, with virtual people. In 1969, we pushed our physical frontier beyond the embrace of the Earth for the first time. Now we have a virtual world and a new frontier—a new moonshot with unusual challenges. Challenges which may end up resulting in the fastest change of all.

With the flood of book reviews I’m still going to try and drop a short essay every Saturday. (Generally shorter than this one, but we’ll see how it pans out.) This means having a Saturday deadline (which is how things worked in the very beginning.) We’ll have to see what emerges. If you want to see what has already emerged (slithered forth? oozed out?) May I direct your attention to the archives. I haven’t said anything about Charlie Kirk, but it did put me in mind of one of my earliest pieces: Godzilla Trudges Back and Forth.

I know the interstate wasn’t done in 1969, but it was about ¾ done, so the point basically stands. I’m also aware that engines are 2-3x more powerful, far more fuel efficient, and drastically less polluting.

I don’t think he uses LLMs that much. He’s got better things to do, like coaching high school robotics.

Consider HAL from the aforementioned 2001. Rosie from the Jetson’s. Asimov’s I, Robot series. Or consider that the first serious attempt at AI was in 1956.

Would the Model T be the moonshot here? It’s possible it could count as the moonshot for several S-curves. Supply chains? Automation? Taylorism?

The moonshot here should be obvious.

I could see getting an extra 10-20 years of life expectancy, but I would bet against immortality. If we’ve learned anything from AI it’s that organic machines are more complicated than we imagined.

One of my regular readers will inevitably bring up the Amish in a discussion like this. And they are a fascinating case of a community that has rejected technology, but are not Luddites. I agree that this statement doesn’t apply to them, but a full discussion of how the Amish fit into something like this is outside the scope of this post.

My great-grandmother was born in 1888 and lived to be 103. My mother was trying to explain this length of time to me as a kid, and she said, "grandma traveled West on horses, read about the Wright Brothers when she was a teenager, and lived to see the space shuttle." What an amazing time to be alive. Even ignoring all the other things: cars, vaccines, refrigeration, washing machine, indoor plumbing, canned food, etc... And I get a dopamine delivery system in my pocket. Yeah, we somehow lost the thread.

In the intelligence explosion idea: Man has been trying to make a perpetual motion machine for millennia The intelligence-explosion / singularity theory is just the digital version of the same. I expect artificial superintelligence to be the "cold fusion" of the IT world -- always just a few years (and a few bigger datacenters) away,.

We've been throwing our most talented people into IT for decades. If the digital S-curve is plateauing, perhaps some of those people will start building real things again. Ironically, Peter Thiel's VC model may have been a cause of his own lament. The real (vs virtual) world could be prioritized via a shift in govt research funding. That was what made the original moonshot.

"Released in 1968, it was meant to be a relatively realistic depiction of what people expected out of the next 30 years: lunar bases, manned missions to Jupiter, and fully sentient AIs. Instead, we have yet to even return to the Moon."

There is another take on 2001, the movie. That is it represents exhaustion with technological advancement. The space station is half finished. The shuttle flies nearly empty. The space hotel is barren and the only guests seem to be gov't workers for the USSR and US using expense accounts. It doesn't show much of life on earth but one gets the sense the earth probably looks a lot closer to what we see today than the Jetsons. It's plausible to even imagine the phone call Dr. Floyd makes to his daughter is received by her ipad on the other side.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cQ3e9q28uOQ