Children of Mars - Sid Meier's Civilization Lied

Back when Rome was just one Italian settlement out of many, but a settlement with a dream!

Children of Mars: The Origins of Rome’s Empire

By: Jeremy Armstrong

Published: 2025

288 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

The deep history of Rome. What we actually know about its legendary founding, its early rise to prominence, and the shape of its military. Additionally, the development of Roman identity and how that identity interacted with the other elements.

What’s the author’s angle?

This belongs to that genre of book which takes recent scholarship and archaeological evidence and uses it to puncture the previous, more simplistic historical view.

Who should read this book?

Military history buffs, or anyone who’s interested in Rome, particularly the period from roughly 8th–3rd centuries BC.

Specific thoughts: How video games get Rome wrong

I am certain that games like Sid Meier’s Civilization and Paradox Interactive games like Europa Universalis have significantly increased the historical literacy of those who have played them. I would say that, on net, they’re a very positive force for historical literacy.1 However, there is one way in which these games give people a very flattened view of the world, especially in the area this book covers.

From the very moment you start playing a game of Civilization as the Romans, your goals are clear: you’re going to conquer the world. You’re not just going to found one city, you’re going to found multiple cities, as many as you can. Your entire civilization is driven by a singular focus, expansion and domination. And there are definitely no issues of identity. You are the ROMANS!

To be fair to these games, there are numerous limitations. You want the game to be fun to play for a single person, and there’s a limit to the amount of complexity you can add, particularly if you also want to simulate the passage of hundreds of years.

Furthermore, not only is this a feature of video game design, it’s also a feature of the way history is written—by the Romans themselves! Quite a bit of the “history” we get from actual Roman writers is colored by a desire to portray Rome as a city with a destiny. A city that was always aware of its glorious future, and its special place in the world.

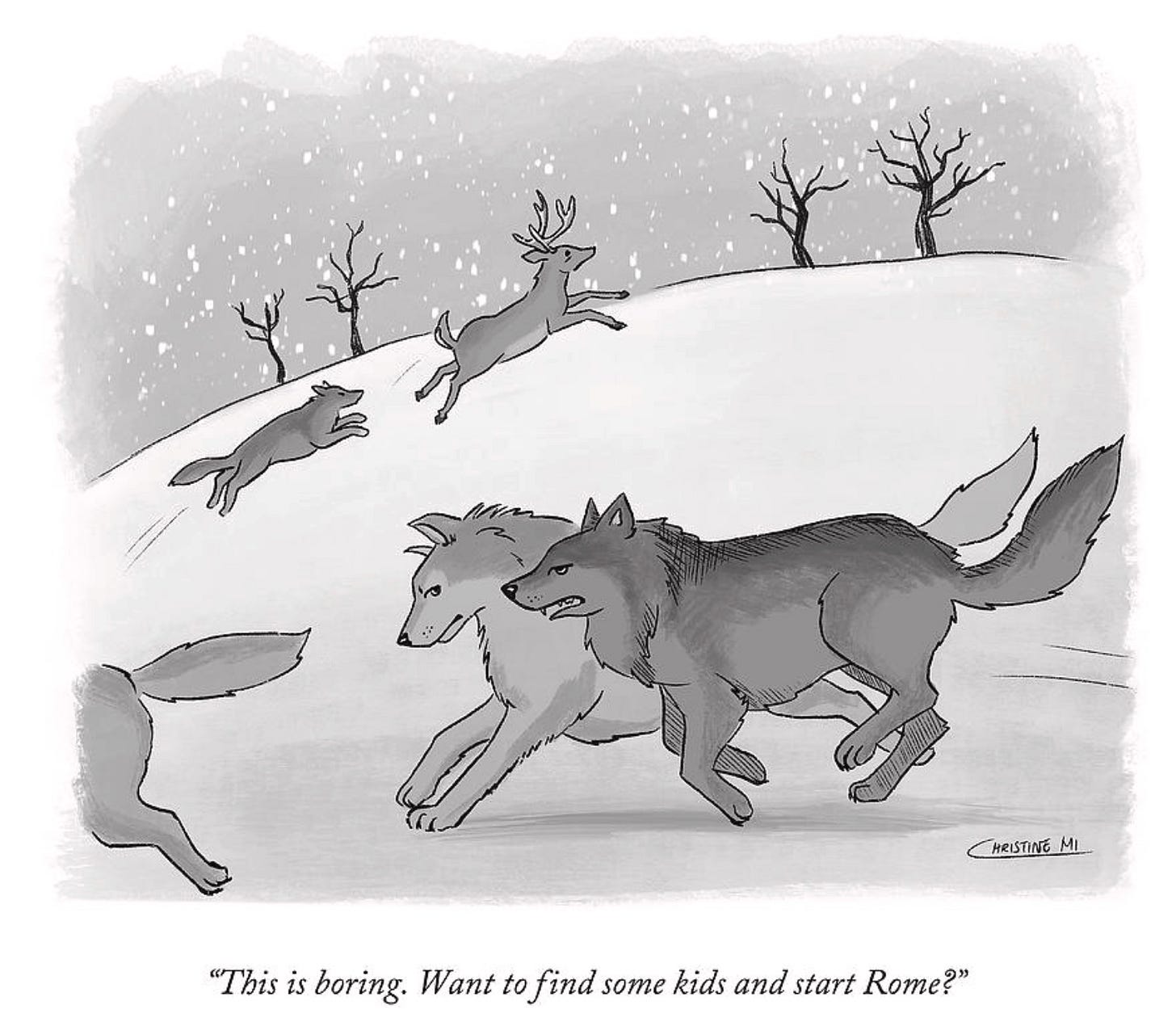

Livy portrays early Rome in much the same fashion as the game Civilization. From the moment of the city’s founding by Romulus, it was apparent that it was the first of many cities, and that they’d better start scouting the surrounding countryside in search of the next city site.2 (Plus who knows when you might need to kidnap some wives.3) Livy doesn’t quite describe it in exactly these terms, but in his history the glorious destiny and identity of Rome, as “Rome!” was there from the very beginning.

Armstrong is here to tell you that this is not the case. Not only is the idea of Roman destiny basically a retcon—Rome wasn’t much to imagine a destiny around. In the beginning Rome wasn’t a city-state like Athens or Sparta, it was more of a gathering place where various Italian clans/families coordinated.

As always, deep history is difficult. You’re trying to put together a puzzle where all but a handful of pieces are missing. Still, the idea of the tribe is a useful place to hang our hat. Perhaps if you’ve studied any Roman history you’ve heard of the 35 tribes. But by the time we arrive at the history people are familiar with (Caesar, end of the Republic) these tribes are just a way of keeping track of people, without much if any connection to a person’s actual identity. But in the early days, tribes represented something real. Actual clans and families which were Roman only in a loose sense.

In the sixth century BC, historians are somewhat confident there was a reorganization of tribes, which ended up creating four “urban” tribes and fifteen “rural” tribes. But even then using the word tribes probably gives one an exaggerated sense of the size. They really were just families, and manpower-wise Rome was still pretty weak. It was another 200 years before Rome got around to conquering the nearby city of Veii, and by nearby I mean it was 7 miles to the north.

At that time that was considered unusually aggressive. War mostly consisted of raids and short battles featuring champions. Actual expansion and conquest, of the kind you imagine if you’ve played too much Civilization, mostly didn’t happen. And despite this show of strength, a few years later, Rome itself was sacked by a band of 5,000 Gallic mercenaries which happened to be passing through on their way to Sicily.4

All of this leaves us with the question: if Rome was just a hub where some families coordinated around mutual defense and trade, and if it was just one of dozens of such hubs in ancient Italy, how did they end up being the one that went on to conquer so much of the world?

Armstrong doesn’t provide a really concrete answer. There wasn’t some singular change, or a uniquely talented leader, or a particular bit of culture the Romans possessed and everyone else lacked. The clans associated with Rome were just better at scaling up the normal Italian customs of power and obligation. They didn’t do anything different, they were just better at doing what everyone else was doing. Clans were always uniting together for mutual defense. Rome was slightly better at systematizing it. The Roman clans were bound together a little bit tighter, and when an army needed to be raised, that allowed them to raise one slightly larger than their neighbor. This made them a little bit stronger and encouraged other clans to join them. (After the sack of Rome by the Gauls, four more tribes were added from the remnants of Veii.) This organization snowballed until eventually things really took off, but over the course of centuries.

We want to imagine that there was something special about Rome from the very beginning. The Romans themselves fell into this trap. But in reality, a lot of stuff is just people getting lucky, and you never know how long that luck is going to last. In Rome’s case it lasted a very long time.

—----------------------------------------------------------------------

I came across this book in an episode of the very excellent School of War podcast, hosted by Aaron Maclean. I hesitate to recommend an entire podcast. If you take one of my book recommendations you’re only looking at 10-20 hours (mostly) but a podcast recommendation might end up being hundreds of hours. Still this is a pretty good one. Speaking of recommendations and luck. Hopefully I’ll be lucky enough to get a recommendation from you. Perhaps you could recommend it to the members of your clan.

This is not to say that the time it takes to play these games couldn’t have been better spent. I’m sure a well crafted reading program or (these days) a dialogue with a good LLM would yield more “historical knowledge per hour”.

A “Scout” unit is typically the first thing you build in Civilization once your first city has been founded.

Not part of the game Civilization but very much a part of early Roman history.

The ancient sources put it at much higher, but Armstrong thinks 5,000 is closer to the mark. The idea that they were mercenaries is part of the tradition, but can’t be substantiated.