Chasing My Cure - A Catastrophe of Chaotic Castleman's Crises

...Chiefly Caused by Cytokine Cascades!

Chasing My Cure: A Doctor’s Race to Turn Hope into Action

By: David Fajgenbaum

Published: 2019

256 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

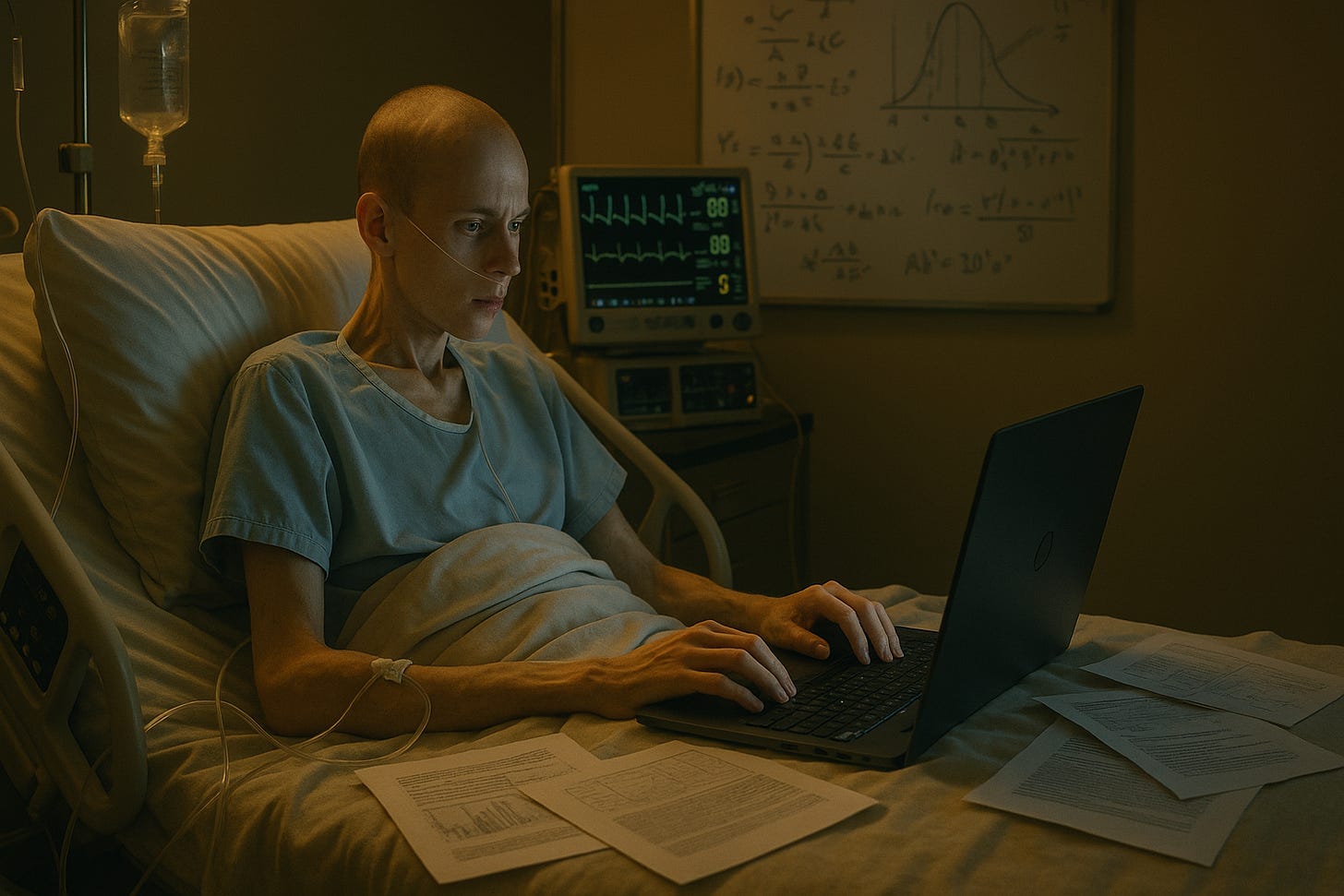

Right as Fajgenbaum was finishing up the exams for his third year of medical school, he was struck by his first attack of idiopathic multicentric Castleman disease. It nearly killed him (last rites were administered). He went on to have four more attacks, each of which also nearly killed him, but somehow in between attacks he was able to research the disease enough that he eventually found something (rapamycin) which has (so far) kept additional attacks from happening. As an outgrowth of his own research he founded the Castleman Disease Collaborative Network.

What’s the author’s angle?

This is one of those cases where the author has a large “angle”, Fajgenbaum has Castleman disease, and is very much advocating (in the course of the book) for more research and more funding for the treatment of the disease he has. This is not a bad angle, but there is a lot of advocacy in the book.

On the other hand the fact that he has the disease is also one of the book’s great strengths. It creates a compelling story, and a fascinating approach to the research and cure of the disease.

Who should read this book?

I think it’s most interesting for those who want to understand how medical research is done. Its failure points, but also its potential for life-altering outcomes. Fajgenbaum’s personal story is also very interesting, and people who just like good biographical stories will also enjoy it.

Specific thoughts: How much should this story be read as an example of broken science?

Before Fajgenbaum contracted his disease he subscribed to what he terms the “Santa Claus theory of civilization”. I’ll let him explain it:

When I set out to be a doctor, I had already borne witness to incurable disease and inconsolable sadness—my mother had died of brain cancer when I was in college—but I was still optimistic about the power of science and medicine to find answers and cures. Because to be honest, long after I could reasonably blame it on youth and naïveté, I basically believed in the Santa Claus theory of civilization: that for every problem in the world, there are surely people working diligently—in workshops near and far, with powers both practical and magical—to solve it. Or perhaps they’ve already solved it.

That faith has perverse effects, especially in medicine. Believing that nearly all medical questions are already answered means that all you need to do is find a doctor who knows the answers. And as long as Santa-doctors are working diligently on those diseases for which there are not yet answers, there is no incentive for us to try to push forward progress for these diseases when they affect us or our loved ones.

After coming down with Castleman’s Fajgenbaum realized that there wasn’t a Santa-doctor for every disease, at least not for his disease. If he wanted to figure out a cure, he was going to have to more or less do it on his own. Which is not to say he didn’t get a lot of help from other doctors, as he’ll be the first to admit, merely that there was no one more interested in his disease than him, and no one better positioned to make progress towards understanding it. But he (and I) wondered, why this should be. Why hadn’t anyone else brought his level of focus to the problem?

Fajgenbaum’s answer mostly comes down to the sheer number of medical mysteries, rare diseases, and biological complexities. Outside of that he notes he had a hard time getting people to take him seriously as a researcher of Castleman’s while also being someone suffering from it. The people most focused on the problems inherent to a rare disease are often excluded from the process of curing it.1

Fajgenbaum’s explanations cover a lot of the problem, but I think it’s worth digging deeper. To begin with, we might imagine that this lack of focus is a good thing, that we shouldn’t be spending very many resources on curing rare diseases. Rather, EA style, our dollars should go where they can prevent the most death and suffering. The fact that Castleman’s wasn’t getting as much attention as breast cancer and prostate cancer are, is a feature not a bug.2

There’s probably some amount of conscious resource allocation going on, but the sense I get from the book, combined with stuff I’m reading elsewhere, inclines me to believe that research has become encapsulated in incremental PhD paper-sized chunks. And you don’t get a PhD by taking a dramatic swing, you do it by adding a small amount of knowledge to something that’s already getting a lot of attention and funding. But if you’re going to die if you don’t figure it out, like Fajgenbaum, and if you also have the resources and connections necessary to do the research, also like Fajgenbaum, then you can make far more substantive advances. And if we’re going to have Santa Claus doctors it’s going to require these bigger swings, of the sort Fajgenbaum is engaged in.

The question is, does every advance require nearly killing an incredibly motivated medical student?

In a similar fashion to the way Fajgenbaum was chasing a cure, I’m chasing posts. (Yes, I know it’s a weak analogy, but not everything is going to be a masterstroke.) As part of the chase I had intended to keep a schedule. I don’t know how many of you actually noticed or cared. Initially I was going to try to burn through my backlog of reviews as quickly as possible. As such, I hoped to publish Monday, Tuesday, Thursday and Friday, with a short essay on Saturday. As you might have noticed, that was already starting to break down, and it’s only going to get crazier. Somehow I’ve ended up with a trip every weekend for the next four weeks. Nevertheless I’m still hoping to get out at least three pieces every week. If I don’t it’s not because I don’t love you guys, it’s because I love the Truth (leisure? Ding-dongs? naps?) more.

I read this book along with my daughter, who does medical research. She said the kind of patient-led research Fajgenbaum describes is getting more common, and that she’s involved in a group that it designed to work closely with patients.

Of course if we were going to go full EA we’d be spending money on deworming initiatives and mosquito nettings, or AI Risk…

Maybe naming things gives us a false impression of a limited spectrum of disorders and diseases.

Sure, the spectrum is actually limited, but the potential space for damaging alterations of DNA or pathogens is vast. Symptoms can overlap, and the fact that something is in a textbook or a report can give a false impression of just how long established the details of it are.