Age of Diagnosis - Words Have Power! (said the blogger)

You’ve heard about placebo’s? Well what about nocebos?

The Age of Diagnosis: How Our Obsession with Medical Labels Is Making Us Sicker

Published: 2025

320 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

The idea that putting labels on something is not a free lunch—like everything else there are tradeoffs. Rather than framing numerous illnesses as being psychosomatic, O’Sullivan seems more to be suggesting that humans are very suggestible. (I get the meta-ness of the statement.) As such, once you generate a label it has a tendency to warp identities, and make people seek out confirming evidence. This all creates a sort of nocebo effect which may increase the severity of whatever symptoms they’re experiencing.

To put it more succinctly, labels have power and we should be circumspect about applying them.

What’s the author’s angle?

O’Sullivan is a neurologist who noticed that lots of patients have “normal” tests, but are also indisputably suffering. As someone more focused on the brain than other parts of the body, she has long contended that expectations, culture, current fads, etc. play a much bigger role than most doctors want to admit. It’s not all about biology, psychology also has a role. Previous books include It’s All in Your Head: True Stories of Imaginary Illness and The Sleeping Beauties: And Other Stories of Mystery Illness.

Who should read this book?

Anyone interested in a broader discussion of how the world outside of medicine interacts with the world of medicine. How the epistemic crisis, culture, disease advocacy groups, bureaucracy, and patient longing all affect the act of putting a label on a cluster of symptoms.

What does the book have to say about the future?

As with many books I review in this space, this book maps out a trend, a trend that appears to be moving in the wrong direction. Not only are labels and people with labels proliferating, but it’s also becoming more difficult to be treated or even to interact around a set of symptoms unless it’s in a bucket with a label on it.

O’Sullivan also worries about the pre-patient and the liminal patients. Diagnostic tools just keep getting better and better while our ability to treat what we uncover isn’t keeping up. Lots of genetic screening ends up giving probabilities for future conditions, and you can imagine a collection of biomarkers that have a slightly higher chance of being present in someone with this or that diagnosis, but also might mean you’re entirely symptom free. Our urge to label is relentless.

Specific thoughts: Which direction is a diagnosis pulling us in?

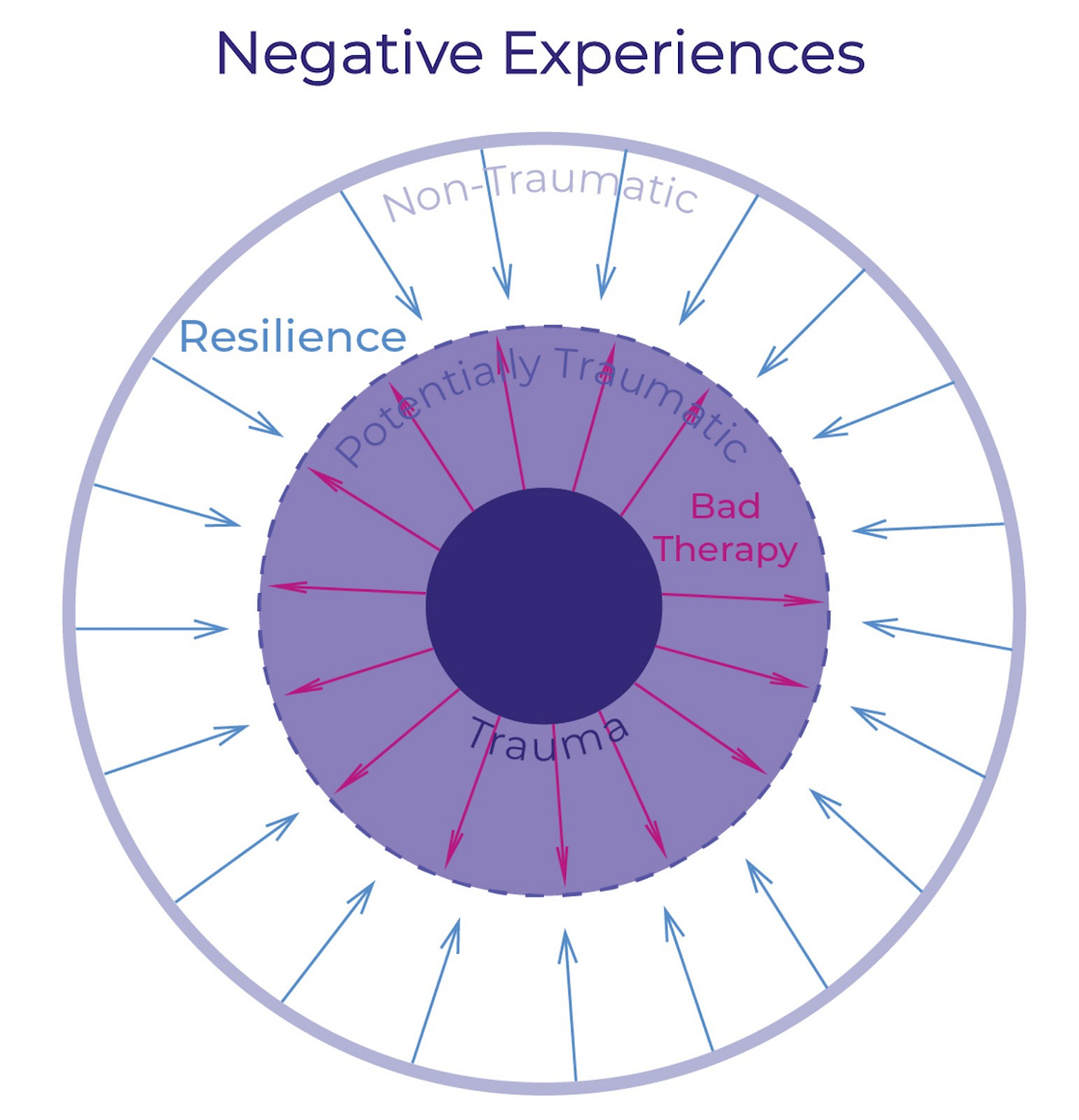

The mechanism described by this book reminds me of the same mechanism I described in my review of “Bad Therapy”. In that review I described how “Bad Therapy” takes things that are potentially traumatic and solidifies them into actual trauma. While resilience takes things that are potentially traumatic and defuses them. Here’s the final image I used to display this process:

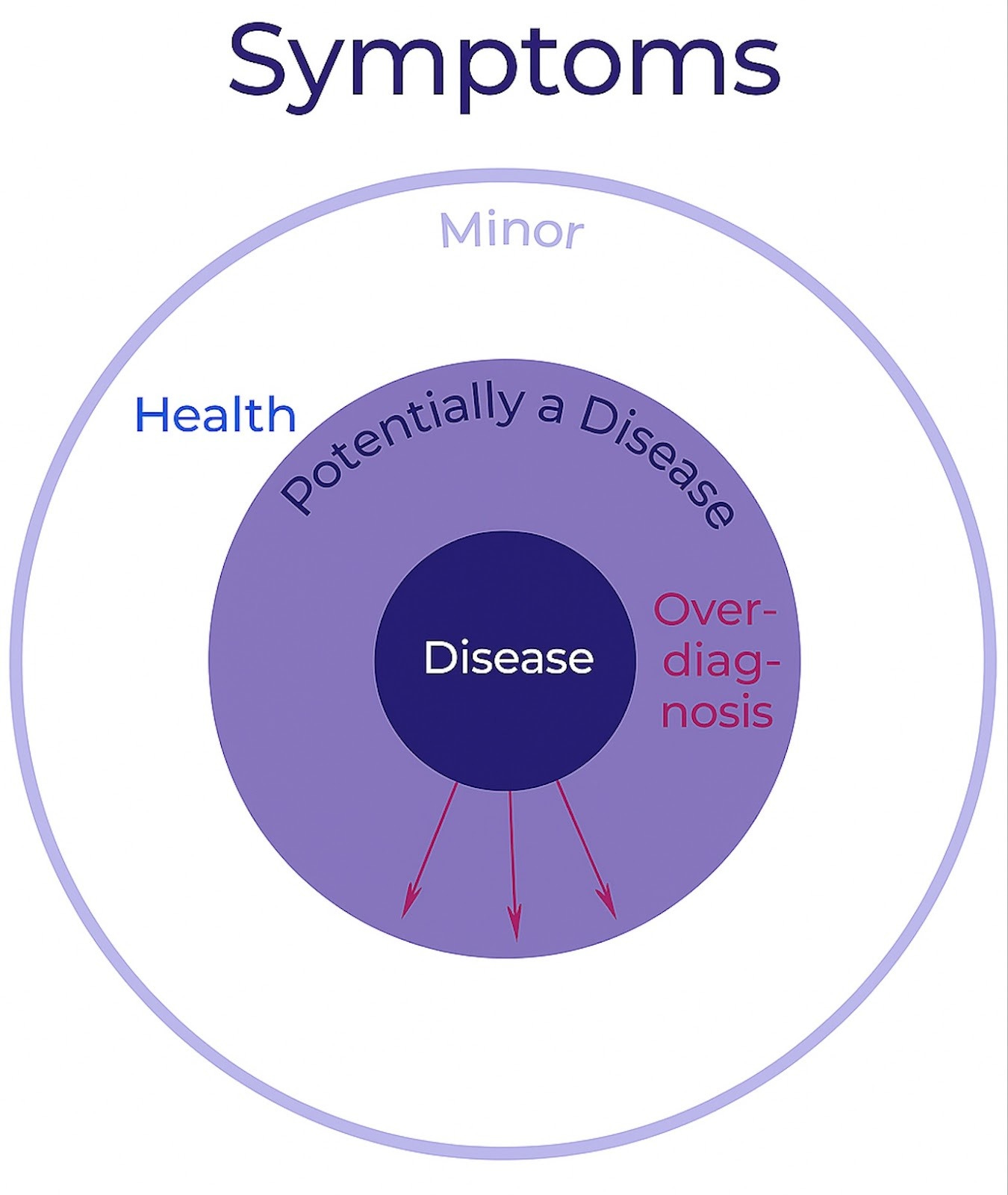

You can imagine that O’Sullivan is describing a similar process when it comes to diagnoses. At the center you would have actual diseases where a diagnosis helps out a lot, and gives you a clear path forward (think TB, or a broken bone, or a very specific cancer diagnosis.) Around the exterior you have health, or at least the strong perception of health. O’Sullivan argues that over-diagnosis pushes the disease circle into realms where there isn’t a clear path forward except to say that you’re definitely not healthy because it’s crowding out the circle of “normal” and “healthy”. In response we should push back on this, and keep the white part of the circle as big as possible. We want people to default to a perception of health rather than a perception of illness. I had ChatGPT modify the graphic. It did okay, not great, but not bad for ten minutes of prompting.1

So far this may seem entirely unobjectionable. I think for most people it is. Where emotions start flaring is when you apply this framework to specific diseases. O’Sullivan applies her framework to Lyme disease, long covid, autism, ADHD, depression, and neurodiversity. She isn’t saying that all of these things are psychosomatic (though some of the more negative reviews of her book have claimed that). Rather, she’s saying that it’s possible they’re being overdiagnosed, and if this overdiagnosis results in more suffering rather than less, that’s bad.

How might overdiagnosis result in more suffering? How might it be bad? If the diagnosis makes you feel worse through some form of nocebo effect, without offering any additional relief through greater targeting of treatments. Then that would be a bad tradeoff. The devil lies in how often a diagnosis would result in such a nocebo effect. I think O’Sullivan would answer “more often than you might think”.

Though this is very tricky territory. In addition to the conditions listed above she also talks about people’s decisions on whether to get genetic testing for risks where if you have the gene the disease is certain. It might be said that you already have the disease. She uses the example of Huntington’s disease. On the one hand this is entirely different from the other conditions mentioned. There is no ambiguity, there is no spectrum. If you have the gene for Huntington’s disease you’re going to develop it, if you live long enough.2 So, should you “get the diagnosis”? She talks about people with that risk, (it’s 50% heritable) and how every little symptom feels like a confirmation that they have it even before the testing, but that also if they get the test then they know that the symptoms are probably the result of it, and it casts a pall over the rest of their life.

In other words, the mind can have a powerful effect on how you interpret the presence of symptoms and their severity. O’Sullivan is asking us to be more careful about how we use this power—the power to direct the mind’s attention through the application of a “diagnosis”.

I think we see here one of the big advantages of doing lots of book reviews. I can reuse graphics, and pad my word count by incorporating stuff I’ve already written. Oh? You want there to be some advantage for you, not just for me? I suppose something, something “understanding the world better” something, something “connected whole” something something “you’re welcome!” If you are interested in the something, something “connected whole” part of that, consider browsing the archives. If you’re looking for something specific feel free to leave a question in the comments and I’m happy to help out.

It’s missing the blue arrows pointing in. And it got rid of a lot of red arrows. Perhaps it has some problem with arrows?

I understand that there’s actually a penetrance factor, and that here we’re talking about “full penetrance”.

I've been recently diagnosed as having ASD (autistic spectrum disorder) level 1. This helped me a lot to understand the causes of my suffering (repetitive work burnouts) and it is helping reorient my professional career to the type of tasks where I excel, avoiding burnout (at least that is the plan). For me it has been great to get the diagnosis (from two different doctors that don't know each other) and it has also been good for my family. They now understand my behavior.

At the same time, I see a lot of people that want to be ASD, they want to be something, they want to be special.

So, this is a topic that must be approached with a lot of nuance, because a diagnosis can be positive or negative, according to the context.