The Wager - A Real Life "Lord of the Flies"

I actually never got around to discussing the Lord of the Flies element of this book. But trust me it’s in there!

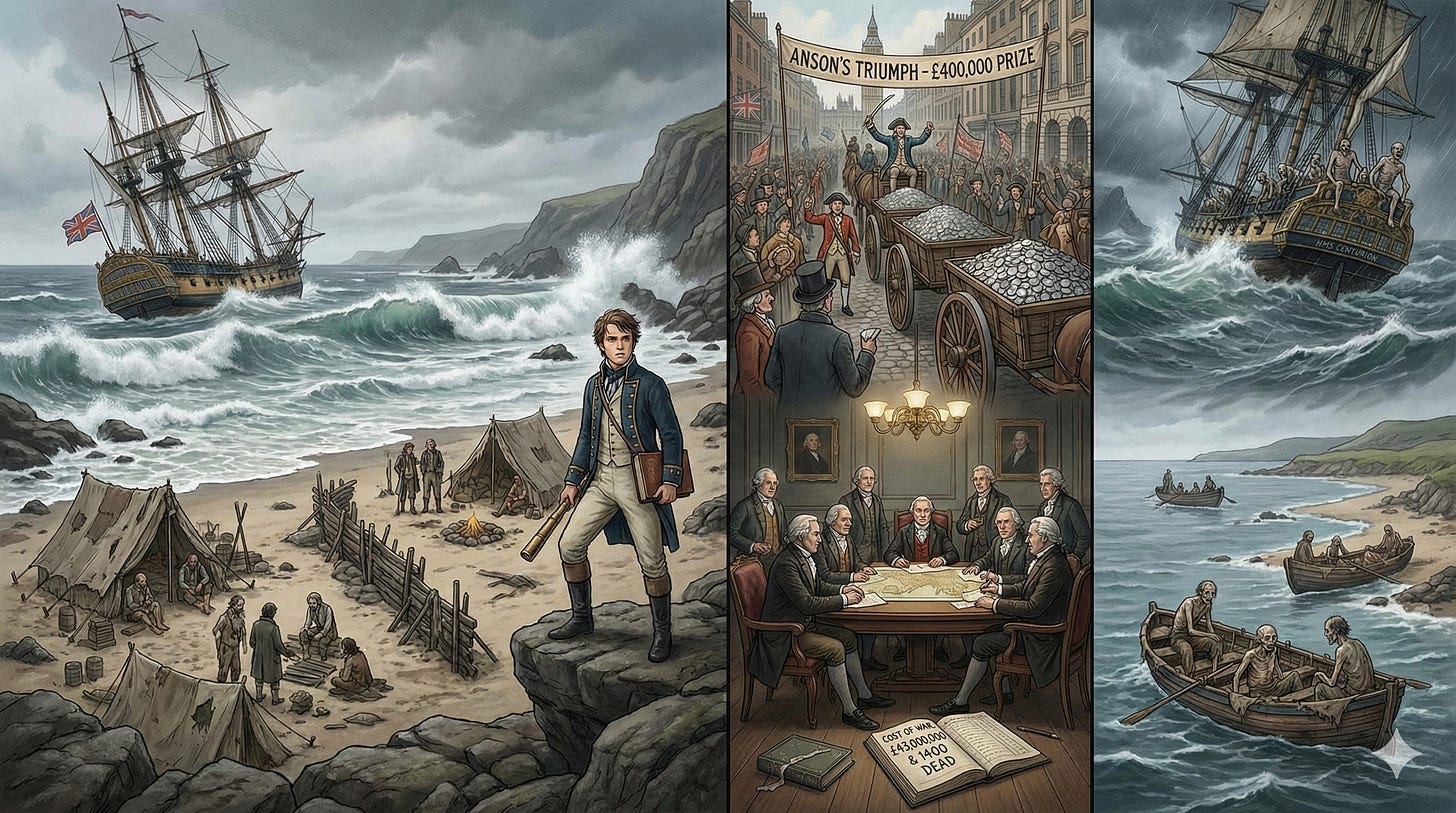

The Wager: A Tale of Shipwreck, Mutiny and Murder

By: David Grann

Published: 2023

352 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

This book is about what happened to HMS Wager, a Royal Navy ship that was shipwrecked on the south coast of Chile in 1741. The journey before the shipwreck was brutal, and it only got worse from there. Out of an initial crew of roughly 250, only about 36 eventually made it back to England.

What’s the author’s angle?

Grann is a writer for the New Yorker who has written three books centered around unearthing interesting and often tragic historical events. His first book was The Lost City of Z. (Which I have read, and it was quite good.) His second and best known book is Killers of the Flower Moon (which I have not read). This is his third book in that same vein.

Who should read this book?

I quite enjoy books like this: true survival stories, particularly those framed by ambitions and sensibilities we can barely imagine in 2025. It’s also history at its pointiest, the tale of a single ship, and really just a handful of men. (The book largely focuses on just three.) If all that sounds appealing, then I think you’ll like this book.

Specific thoughts: The past is a foreign country: they do things differently there

I discovered this book through a post on Manuscriptions, Eleanor Konik’s excellent blog. If you want a run-down of the madness of press-gangs, particularly as it relates to the crew of the Wager I would check it out. I’m more interested in the other topic she brings up, which can be summarized as “What were they thinking?!?”

To back up a little bit, the Wager was part of a squadron of eight British ships commanded by Commodore Anson. His mission was to take his ships from England through the Drake Passage and into the Pacific in order to harass the Spanish during the War of Jenkin’s Ear. The whole expedition was ridiculous from the very beginning. Konik touches on how it was farcically understaffed, and unprepared, so I’d like to focus on another reason it was ridiculous: scurvy.

At the time no one knew exactly what caused scurvy or how to prevent it. And on a voyage of this length any sober assessment would put the chances of scurvy at 100%. And yet these odds never seemed to factor into anyone’s calculation on the wisdom of proceeding on such a voyage. Maybe I’m making too much of this one condition, because the chances of typhus, malaria, bad weather, and a host of other potential catastrophes was also quite high. But there was an inevitability to scurvy that didn’t exist with those other conditions. You could imagine getting fortunate with the weather. And you could imagine that even if you did end up with a typhus outbreak, that it might be contained, and that not everyone would come down with it. But scurvy basically happened to 100% of people 100% of the time on a voyage of this length, and I assume that on some level the lords, the captains, and the sailors all basically understood this inevitability.

Konik covered the insanity of those ordering the expedition, and also the people who were forced to go, but what about the people who presumably knew about the dangers, about the inevitability of scurvy and choose to go. Was there anyone who wanted to go?

Apparently Midshipman Byron did. For this and many other reasons he was definitely the most fascinating character in the book. He was the (eventual) grandfather of Lord Byron, the famous poet, and he went into the trip with sense of enthusiasm and wonder:

Swept up in the romance of it all, Byron began what would become a habit of excitedly filling his journals with his own observations. Everything seemed “the most surprising” or “astonishing.” He noted unfamiliar creatures, such as an exotic bird—“the most surprising one I ever saw”—with a head like an eagle and feathers that were “as black as jet and shined like the finest silk.”

That was at the beginning of the voyage, but even after suffering all of the privations, the scurvy, the typhus epidemic, and all of this for five ridiculous years before finally making it back to England, he stayed in the navy. And less than a year after his return he was given command of his own ship. He not only stayed in the navy, he eventually rose to the rank of Vice-Admiral of the White, which was the fifth highest rank in the entire Royal Navy.

I’m sure that part of his decision came from a lack of opportunity. (As the second son of a failing estate he had “few means to earn a respectable living”.) And lack of opportunity does explain some of the crazy attitudes and decisions of the time, but not all. The expedition, still being led by Commodore Anson, did capture a Spanish galleon that was loaded with treasure. Though by that time he was down to a single ship. And he eventually made it back to England. When he did finally return, his expedition, which had started with around 1900 men, was down to 188. Not all of those people died, though most of them did. A couple of ships turned back in Drake’s Passage, so when you take those sailors into account, plus the 36 who survived from the Wager, you end up with around 500 men who survived. So a fatality rate of around 70-75%, nearly all of whom died of typhus or scurvy.

It’s hard to imagine any sensible rationale for the expedition in the first place. But people are often unreasonably optimistic about the future. However, once the expedition is over and the final tally is known, it’s hard to imagine, even with the capture of the treasure, that the whole thing could be viewed as anything other than a debacle. This would certainly be the case if we applied the standards of today. That is not what happened at the time. It’s not unsurprising that Anson was hailed as a hero. It is surprising that no one was called out as a villain.

Were they blasé? Callous? Brave? Reckless? All of the above? Whatever it was, a large group of people all decided to either sanction or participate in a hugely risky endeavor. Obviously some people were forced into it. But many of them obviously thought it was completely natural. Why wouldn’t you sail eight ships through the most treacherous waters in the world? On an expedition to the far side of the globe? An expedition that would surely result in massively debilitating scurvy, and unless people were extraordinarily lucky, typhus, malaria, and shipwrecks.

Are we blessed that no one can even imagine an expedition of this sort any longer? Or are we cursed to live in an age devoid of danger, adventure, and mystery? Certainly I am very glad that neither I, nor any of my sons will end up shipwrecked on a far away island (or more likely dead from scurvy or typhus somewhere along the journey). But at the same time, I wish I could have looked into the eyes and shook the hand of Vice Admiral of the White, John Byron.

This book did fill me with the desire to sail through the Drake Passage. Which is odd, since I’m not exactly immune to being seasick and apparently waves can reach 40 feet? I still think it’d be a cool bucket list item, but I’m obviously no John Byron. As to who I actually am? Much is revealed in the archives, and much will yet be revealed in the future. If those revelations seem interesting (will he ever sail through the Drake?) consider subscribing.