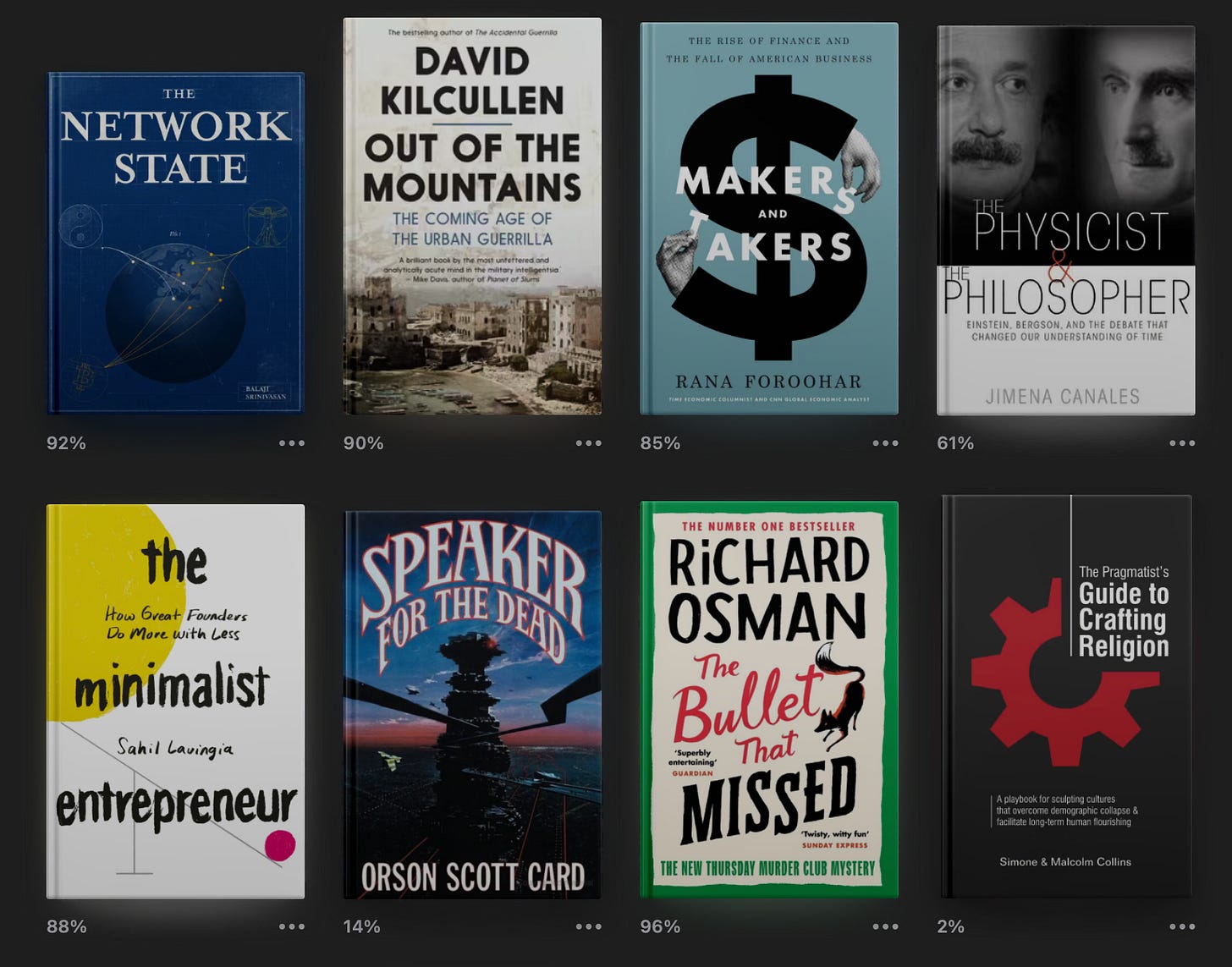

The 10 Books I Finished in May and One I Didn't

Didn't finish in May that is. I finished it back in September, but it was only just now published...

The Network State: How To Start a New Country by: Balaji Srinivasan

Out of the Mountains: The Coming Age of the Urban Guerrilla by: David Kilcullen

Makers and Takers: The Rise of Finance and the Fall of American Business by: Rana Foroohar

The Physicist and the Philosopher: Einstein, Bergson, and the Debate That Changed Our Understanding of Time by: Jimena Canales

The Minimalist Entrepreneur: How Great Founders Do More with Less by: Sahil Lavingia

The Ethics of Aristotle by: The Great Courses and Father Joseph Koterski S.J.

The Disappearance of Josef Mengele by: Olivier Guez

Speaker for the Dead (The Ender Saga #2) by: Orson Scott Card

The Bullet That Missed (A Thursday Murder Club Mystery #3) by: Richard Osman

The Sandman: Book Two (The Sandman #2) by: Neil Gaiman

The Pragmatist’s Guide to Crafting Religion: A Playbook for Sculpting Cultures That Overcome Demographic Collapse & Facilitate Long-Term Human Flourishing (The Pragmatist's Guide #5) by: Simone H. and Malcolm J. Collins

May felt busy, but it is nothing compared to what I have going on in June. Of course, part of May’s busyness was trying to get ahead on my writing so that I could be in Europe for two weeks and actually enjoy it. This busyness included a big pivot: you’re now reading this on Substack. Welcome!

Also, my basement flooded in May. The HOA turned on the sprinklers for the first time. I guess a valve or something was broken for one of the zones near our house and the sprinklers ended up running for, near as I can figure, fifteen hours. Fortunately it didn’t flood the whole basement, just a half circle of carpet in a radius of about eight feet. It also ruined the drywall under the window, but we didn’t have anything on the carpet that could be harmed by sitting on what was, essentially, a saturated sponge. Though definitely extremely aggravating, it wasn’t a catastrophe.

Perhaps the most annoying part is that according to Utah law the HOA needs to have insurance, but it can have up to a $20k deductible, and on amounts below that it’s “no fault” which in practice means it’s my fault, as in I have to be insured for it and that’s who pays for it. Fortunately I am insured and the insurance company is going to pay for most of it (minus my own deductible). But given that it was entirely the HOA’s fault it’s annoying that my insurance takes the hit…

I- Eschatological Review

The Network State: How To Start a New Country

Published: 2022

474 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

The emergence of a new leviathan. Where previously there was only God and the state, a new leviathan has recently entered the scene: the network, powered by cryptocurrency.

What's the author's angle?

Srinivasan is a huge advocate of cryptocurrency and was the first CTO of Coinbase. Outside of that he’s been one of the primary evangelists for web3. Recently he lost a bet that in 90 days bitcoin would go to $1 million as a result of hyperinflation. Clearly he’s not a disinterested party in the crypto discussion.

Who should read this book?

If you want to know what all the fuss is when it comes to crypto — the vision for crypto — above and beyond investing in it, this is the book for you.

General Thoughts

Perhaps my all-time favorite science fiction world is Neal Stephenson’s The Diamond Age. The book describes a near future world where humanity is split up into ideological tribes. These tribes have enclaves all over the world. Territorially-bound nation states no longer exist. The Network State describes how this science fiction plot might become a reality.

Given my affection for Diamond Age I was very much predisposed to like The Network State, and I mostly did. But like many people sketching out their vision for the future I thought Srinivasan focused too much on the cool opportunities and not enough on the difficulties.

The big opportunity Srinivasan sees is the one presented by cryptocurrency. Nor is he alone in this. Many people imagine that crypto will remake the world. Srinivasan asserts that it would allow people from all over the world, of a similar ideology, to connect and set up states in much the same way Stephenson does. Srinivasan imagines enclaves scattered over the world connected financially and logistically by cryptocurrency. In addition to Diamond Age it also reminds me of the archipelago idea that Scott Alexander came up with many years ago. It's a very cool vision of the future, much better than the culture war hellscape we currently inhabit. And there’s no reason that amazing network states couldn’t be formed in exactly the fashion Srinivasan describes. Well… except for the fact that current states are definitely not going to be on board with the idea.

This takes us to our first difficulty. To discuss it I’d like to bring in another book I read this month, Out of the Mountains by David Kilcullen (the very next review).

Both authors explore small-scale organizations that wish to take on larger organizations. Kilcullen describes terrorists who use violence to take on states or become them (in the case of the Taliban) while Srinivasan describes, presumably, upright citizens who use crypto to exit a state and create their own state. Of the two, Kilcullen has a greater appreciation of the difficulties because his discussion centers the violence, while Srinivasan almost entirely ignores it.

To illustrate why violence or the threat of violence is so important Out of the Mountains includes a quote from Mao Zedong:

Every Communist must grasp the truth, “Political power grows out of the barrel of a gun.” Our principle is that the Party commands the gun, and the gun must never be allowed to command the Party. Yet, [by] having guns, we can create Party organizations . . . We can also create cadres, create schools, create culture, create mass movements. Everything in Yenan has been created by having guns. All things grow out of the barrel of a gun.

Srinivasan imagines that political power might grow out of the blockchain instead of the gun and he eloquently describes how that might work. The blockchain provides stateless currency and an unalterable record of historical events. In very broad terms Srinivasan describes this as “exit” and “voice”. But he doesn’t spend any time discussing how this new political power will supplant the old physical power. Yes, it is true that it’s somewhat pointless for the police to show up at your door with their guns and say “Turn over all your bitcoins!” (Though I think it’s more effective than crypto enthusiasts want to admit, and it doesn’t have to be the police.) But what happens if they show up at the offices of Coinbase and do the same thing?

It is true that, at least in the short term, the government won’t do anything so crude. But in the long run, if people are using crypto to exit the state (which for most people means not paying taxes) something like this would happen. And in the short run they don’t need to show up with guns. Everytime there’s a hint at a new regulation the price of bitcoin and other crypto falls against the dollar. Which illustrates another weakness, there’s still the fact that you mostly have to convert crypto to a state backed currency in order to use it.

Of course, you don’t have to hold your crypto in Coinbase or some other exchange the government can exert pressure on. You can keep it all in a wallet on your computer. But as mentioned above, don’t think that the government can’t or won’t exert pressure directly on you, but even if they don’t this touches on yet another difficulty.

The second difficulty is technical. How many people want to go to the hassle of managing their own wallet? Obviously some do, but are there enough such people that network states could reach viability?

Clearly there’s the whole population of the dark web, which Srinivasan might call a proto-network state, but their motivation for keeping their own wallet and dealing with all the hassles that entails is pretty clear. And the state is still out there. Imagine that they banned the distribution of crypto wallets through all the normal venues. If you had to get your wallet from a torrent site, and maybe you could only run it on Linux. I’m not saying that this is going to happen. I’m saying that states take people trying to break away from their control very, very seriously. Furthermore this seriousness isn’t just in direct proportion to how serious network states are, it actually escalates faster. Imagine that for every level of seriousness people developed about creating a network state, the current state would respond with five levels of seriousness towards stopping it.

Should Srinivasan put out a second edition (or end up reading this review) I suggest that he include an “answers to objections” section. I assume if I were talking to him directly he would have responses to all of my points. Whether I would be convinced by them is another matter, but it would be nice to at least know what they are.

Eschatological Implications

The book felt very US-centric, which seems like the wrong way to approach the problem as the US is probably one of the worst places to try to pull off a network state. Srinivasan makes much of the need for a network state to receive diplomatic recognition. Wouldn’t such a thing be much easier to accomplish in a less-developed country? As an example I’m thinking of the charter city movement, with places like Prospera in Honduras.

It appears that part of why Srinivasan focused much of his attention on the US is that he feels like it’s weak and tottering. That shortly this advancing decrepitude will allow an opening for network states. As support for this attitude he mentioned the predictions of Peter Turchin and Ray Dalio, while explicitly rejecting those of Peter Zeihan. I too am somewhat bearish on the US, but nothing happens as fast as you think it will, and as Adam Smith said back in the day, there’s a lot of ruin in a nation. This is to say a nation as big and as powerful as the US does not go down easily.

By the end of the book I remained unconvinced that The Network is a third leviathan. I suppose it could be, but it’s too early to say. However, for the moment let’s grant that it is and that we’re hurtling towards a clash between the leviathan of The State and the leviathan of The Network. What will this clash of leviathans look like?

Srinivasan seems to imagine that it will go pretty smoothly, but that’s not at all how it went down when the leviathan of religion and the state clashed. One place to locate that clash would be the 30 Years War. Srinivasan mentions that war and the subsequent Peace of Westphalia. The 30 Years war was incredibly bloody and destructive. That’s an example of what happened the last time leviathans clashed. Would something similar happen the next time?

Even if Srinivasan is right, there’s a significant amount of chaos he’s overlooking between where we are now and his desired destination.

II- Non-Fiction Reviews

Out of the Mountains: The Coming Age of the Urban Guerrilla

By: David Kilcullen

Published: 2015

352 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

The world will increasingly be “crowded, urban, networked and coastal” and consequently so will crime and violence. This book explores how that violence will play out.

What's the author's angle?

Kilcullen has been deeply involved in counterinsurgency work for many years. As one example, he helped design the 2007 Iraq troop surge.

Who should read this book?

This book is less about the coming age of the urban guerrilla and more the current age. So if you’re looking for blood-soaked apocalyptic predictions, this is not the book. On the other hand if you’re looking for interesting stories of recent guerrilla attacks, and some short term, reasonable predictions for the future, this might just be the book for you.

General Thoughts

Three things stood out to me from this book.

First, the discussion of how small insurgent groups develop legitimacy through the imposition of order. When you’re living in a state of near anarchy, any lessening of that anarchy, even by means that seem capricious and cruel, is welcomed. Kilcullen’s description of how the Taliban accomplished this is worth reading.

The Taliban publicly announced a set of rules, as laid down by Mullah Omar (who has banned kidnapping for ransom), and then arrested, tried, and executed a gang who had broken these rules. Via placards on the executed kidnappers’ bodies, they sent a message of consistency, predictability, and order, by which they distinguished themselves from corrupt officials. The locals clearly understood this…

In contrast, Afghans whom I asked (during fieldwork in December 2009, the year of the Wardak kidnapping) about their perceptions of the national police or the government court system, just laughed and said that government courts take months to resolve the smallest dispute, cost thousands of dollars in bribes, and render judgments that always favor the most influential power brokers, who can simply ignore the judgment anyway if they don’t like it. By contrast, the Taliban come from the local area, so they understand the issues people are dealing with. Their justice is free of charge, judgments are rendered quickly (sometimes in as little as half an hour), and unlike the Afghan National Police, who are often seen as corrupt and in the pay of local elites, people expect that the local Taliban underground cell will consistently enforce the court’s judgment. “Many people don’t like the Taliban,” a businessman from Kandahar told me, “but at least you know what you’re getting: they’re consistent and fair. You know what to expect from them.”

That line “sometimes in as little as half an hour” cracks me up. It sounds like marketing copy from a TV ad. But, of course, in a sense that’s precisely what it is. The Taliban is marketing to the local populace. Their message is that we will bring order to things, and while you may not like everything we do, we will be consistent and predictable. You will be able to get on with your lives.

The second thing that stood out were the stories. The most fascinating was the story of the raid on Mumbai by a Pakistani terrorist group in 2008. I remember when this happened, but my memory did not really match the actual details of the attack. It was a sixty hour raid (?!) that ranged all across the city, eventually culminating in a standoff at the Taj Mahal hotel. (That’s the part I remember.) All of the details are interesting. But the terrorist group’s ability to run everything from a remote command center was fascinating.

From their tactical operations center in a Pakistani safe house in Karachi, a team of attack controllers…and other Pakistani military and intelligence officers monitored the situation by using cellphones and satellite phones and by tracking Twitter feeds, Internet reports, and Indian and international news broadcasts. Using Skype, SMS text messages, and voice calls, the control room fed a continuous stream of updates, instructions, directions, and warnings to the attackers at each stage of the operation, gathered feedback on the Indian response, and choreographed the assault team’s moves so as to keep it from being pinned down by Indian security forces.

Here’s an example of how this worked in practice:

Despite the chaos, Taj Mahal staff managed to move about 250 people to the hotel’s Chambers area, but terrified guests there soon began using cellphones to call and text their relatives, and in so doing they alerted the media. Indian and international television, Twitter, and Internet news sites soon reported that a large number of hotel guests were trapped, and named their hiding place. Within minutes, the LeT control room in Pakistan, monitoring the media, had passed this information to the assault team in the hotel, who immediately sent a search party to find them. Also at about this time an Indian cabinet minister, trying to reassure the public, announced that India’s elite Marine Commando (MARCO) counterterrorism force was en route to the hotel and would arrive in two hours; this information, which the Karachi control room also passed to the raiders on the ground, alerted them that no response units were yet deployed and that they had a clear window of time to consolidate and harden their position. The terrorists moved about the hotel, taking many hostages at gunpoint; hundreds of others were trapped in their rooms.

Does all this indicate that the modern communication structure will be disproportionately advantageous to guerrillas and terrorists? Or is this a temporary blip? In the future will news stations and law enforcement not be so forthcoming with precise details? I suspect that there will be some correction in that direction, but that over the long run technology will result in irregular forces closing the logistics and reconnaissance disparities which have heretofore existed between them and forces of more developed countries.

Discussion of developed countries takes me to my third point. It’s easy to imagine how this discussion plays out in a place like Haiti, Somalia, or Afghanistan. It’s more difficult to imagine how it plays out in San Francisco or Detroit. Are we seeing the start of something similar here? I would say… “Maybe?”

The answer is “maybe” rather than “no” because Kilcullen introduced me to the idea of a feral city. A city that was once domesticated but has reverted to a wild state. This idea was first proposed by Richard Norton, Scholar at the Naval War College. And San Francisco doesn’t exactly match his definition, but on many measures it is drifting in that direction. (Certainly it’s no longer toilet-trained…) And let’s not forget the example of CHAZ in Seattle.

Obviously our state capacity is still sufficient that we could reverse San Francisco’s slide into ferality, but so far we’ve chosen to let feral cities lie. This is obviously different from the cities Kilcullen discusses in his book, where it’s not the will that’s lacking, but rather it’s the ability. For San Francisco it appears to be the opposite and it’s unclear how that’s going to play out.

Makers and Takers: The Rise of Finance and the Fall of American Business

By: Rana Foroohar

Published: 2016

400 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

How financialization has turned banking from the servant of business into its master. In the process fueling the populism that is currently tearing the country apart.

What's the author's angle?

Foroohar is clearly someone who’s skeptical of capitalism. That said, she writes for the Financial Times so she has a lot of access. This was not written from the sidelines, but the fracas.

Who should read this book?

Probably nobody. This was the SSC/ACX book club book for May, and I think everyone but me hated it. To the point that the book club didn’t even meet because people disliked the book so much.

General Thoughts

The reasons for the hatred heaped on the book by the people who read it ranged from her being wrong about details, to a dislike for her “voice”. Personally I didn’t hate the book, I thought it made a worthwhile point about the distorting effects of financialization. Though I am also reasonably certain there are probably books out there that make the same point in a more cogent fashion.

Regardless of whether Foroohar remains wrong about a lot of things or there are better books on the subject, I still think financialization has distorted the economy in dangerous ways. Of course, you still may be wondering what financialization is. For me it’s best encapsulated by that scene in The Big Short where Richard Thaler and Selena Gomez explain synthetic CDOs. The process by which $10 million of actual mortgage bonds can metastasize into hundreds of millions of dollars of leveraged bets. (As I think about it, The Big Short is almost certainly a better book about this issue.)

Another way of thinking about it is that you have a situation where the people who benefit from the rules are making the rules. I’m not sure whether having a synthetic CDO is ever justified, but I am sure that the people who came up with the idea, and the people who implemented it, did so because they thought they could make a lot of money off of it and not out of any altruistic drive to make the economy run more smoothly.

Rather than go any deeper on a book no one but me liked (and I didn’t love it) here are a few additional thoughts:

I understand the reasoning behind measuring a company’s performance based on its stock price. But has it become an example of Goodhart’s Law? (When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.)

To what extent are all these crazy financial instruments a product of computers and automation? For example would synthetic CDOs even have been possible, logistically, in the 60s?

I think people underestimate the overhang that still exists from 2007-2008 financial crisis and the anger it still generates. I could imagine a technocratic case for all of the ongoing financialization. But just because it’s a good idea doesn’t mean it’s not going to piss people off. Pissed off people are unpredictable, and dangerous.

The Physicist and the Philosopher: Einstein, Bergson, and the Debate That Changed Our Understanding of Time

By: Jimena Canales

Published: 2015

488 pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

A debate about Einstein’s theory of relativity which occurred in the interwar years. Einstein was clearly the leader of one side of the debate, and Bergson was nominally the leader of the other side.

What's the author's angle?

Canalas does her best to be even-handed, but you get the impression that she’s on Bergson’s side in the debate. Canalas doesn’t think that Einstein’s theory is wrong, but rather that Bergson was making some good points about the scope of Einstein’s interpretation of that theory.

Who should read this book?

I was really looking forward to this book and it ended up being mildly disappointing. If you’re on the fence, I would recommend taking a pass.

General Thoughts

Time has a tendency to smooth the rough edges of history. These days Einstein is remembered as a genius who revolutionized physics and Bergson is barely remembered at all. But in 1922, when the debate took place between Einstein and Bergson, the revolution was still ongoing, Einstein’s reputation was still being solidified, and Bergson was a colossus.

Canales takes us through the back and forth, the personalities, the papers, and the principles. She covers a lot of ground, perhaps too much in fact. In the process of covering the debate, along with everything that came before, and everything that came after, it was easy to lose track of the substance of the debate. This was compounded by the fact that Bergson’s point was a subtle one. He agreed with Einstein’s physics, but disagreed with his metaphysics. He had no problem with Einstein’s math, but disagreed with Einstein’s interpretation of that math — namely how time dilation would be experienced. In Bergson's opinion, Einstein failed to understand the subjective experience of time and the intuitive understanding of duration.

Einstein’s primary defense was that Bergson didn’t understand relativity, but Canalas asserts that Bergson comprehended it just fine; rather Einstein didn’t grasp Bergson’s point about subjectivity. Einstein’s stance would be more forgivable if all other scientists were on his side, but big names like Laplace and Poincaré were actually on Bergson’s side.

The debate between the two, both the in-person one in 1922 and the one which took place via proxies, letters, and the opinion of other intellectuals, was interesting. But I found the larger context to be the more engaging aspect.

It was definitely an early example of the coming separation between science and the humanities. C.P. Snow’s famous Two Cultures Lecture wouldn’t take place until 1959.

It was also an example of scientific arrogance. I don’t want to be too hard on Einstein, particularly since in the case of physics arrogance is probably justified, but scientific arrogance spread far and wide and it took a long time for humility to arrive, a process which is still ongoing.

It’s surprising how little attention Bergson gets these days, but my theory is that Bergson’s points about subjectivity ended up being folded into the Copenhagen interpretation of quantum mechanics. On the humanities side, his view was folded into postmodernism where people like Lacan and Derrida ended up overshadowing him.

As I final note, I always wondered why Einstein got his Nobel for the photoelectric effect, rather than for relativity. It turns out it was because of Bergson:

The criticisms leveled against the physicist were immediately damaging. When the Nobel Prize was awarded to Einstein a few months later, it was not given for the theory that had made the physicist famous: relativity. Instead, it was given “for his discovery of the law of the photoelectric effect”—an area of science that hardly jolted the public’s imagination to the degree that relativity did. The reasons behind the decision to focus on work other than relativity were directly traced to what Bergson said that day in Paris [at the time of their debate].

The president of the Nobel Committee explained that although “most discussion centers on his theory of relativity,” it did not merit the prize. Why not? The reasons were surely varied and complex, but the culprit mentioned that evening was clear: “It will be no secret that the famous philosopher Bergson in Paris has challenged this theory.” Bergson had shown that relativity “pertains to epistemology” rather than to physics—and so it “has therefore been the subject of lively debate in philosophical circles.”

The Minimalist Entrepreneur: How Great Founders Do More with Less

By: Sahil Lavingia

Published: 2021

256 pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

Lavingia’s journey from founder of potential unicorn Gumroad to a lean startup advocate.

What's the author's angle?

The book is heavily biographical, and Lavingia, having arrived at this end point in his journey, expects that other potential founders might want to skip right to the end. He has a VC fund to help like minded founders do just that.

Who should read this book?

If you’re thinking about founding a startup and have already read and been convinced by The Lean Startup, this has some additional nuance that will be useful to someone that actually has to execute on all these ideas.

General Thoughts

A reader recently asked me, “You have your own business, why do I never see you review business books?” And while it’s not true that I never review business books. Candidly I should read more of them, given that running a business is my livelihood. Also I picked up a lot of recommendations at the Goldman Sachs 10k Small Business program I did, so you might see one a month here for a while.

I picked up this book because I’ve been interested in Lavingia ever since he moved to Provo, Utah. I tried to get him to go to lunch with me, but he turned me down. The book is pretty good as business books go and his story is interesting, but there’s not much in here that you can’t get from The Lean Startup.

The Ethics of Aristotle

By: The Great Courses and Father Joseph Koterski S.J.

Published: 2013

Audio w/ 64 page PDF

Briefly, what is this book about?

Lectures on The Nicomachean Ethics.

What's the author's angle?

As you can tell from the title, the lecturer is a priest; his take on Aristotle has a religious angle, but not an extreme one.

Who should read this book?

If you have read or plan to read The Nicomachean Ethics I would definitely pick up these lectures. Of all the supplementary material I’ve consumed around the ancient philosophy I’ve been reading this was the best.

General Thoughts

The lectures come with a PDF and I was worried that I’d have to have it open as I listened in order to be able to follow along but that wasn’t the case. Koterski’s delivery was clear and flowed smoothly enough that I could just listen and enjoy.

III- Fiction Reviews

The Disappearance of Josef Mengele

By: Olivier Guez

Published: 2022

224 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

A semi-fictional recreation of Mengele’s life on the run.

Who should read this book?

I’m not sure. When I read the book’s blurbs, I wonder if I somehow ended up reading a different book. This doesn’t feel like an “action-packed” or “shockingly intense” book. But it was originally written in French, and it’s entirely possible those phrases mean something different there than they do here.

General Thoughts

Hannah Arendt wrote a book about Eichmann which was subtitled “A Report on the Banality of Evil”. Something similar is done here to Mengele. The book is based on an awful lot of research, but it’s also clear a great deal had to be filled in — particularly Mengele’s inner monologue. In addition to banal, evil in this book is extremely petty.

The book is an interesting examination of this pettiness. Mengele is upset with his family, despite the fact that they continue to send him money, fixated on his failing health, and angry that his actions have been misrepresented. He’s also obsessed by his status within the German diaspora in South America.

The larger setting of the book was interesting. The picture it painted of the diaspora was revealing, as well as the description of how the world grappled with Nazism after the war. You would think that Mengele would be most hunted in the immediate aftermath of the war and then people would gradually forget about him, instead it was the exact opposite.

The main difficulty I encountered with this book is that Mengele is the main character, and he’s a particularly loathsome and pathetic individual. There’s definitely an important moral lesson there, but it didn’t make for enjoyable reading.

Speaker for the Dead (The Ender Saga #2)

By: Orson Scott Card

Published: 1986

415 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

The further adventures of Andrew “Ender” Wiggins. Who arrives on the planet Lusitania to speak the death of a xenobiologist murdered by the Pequeninos, the alien race he was studying. Ender subsequently becomes enmeshed in the climax of the drama that took place in the twenty-two years it took him to arrive.

Who should read this book?

This is a very different book from Ender’s Game, but still worth reading if you liked that book or Card’s work in general.

General Thoughts

Despite being both a Mormon and a fan of science fiction, I’m not a huge fan of Card outside of Ender’s Game. So while I read this book many years ago, it didn’t make much of an impression. Upon re-reading it, I think it was both better and worse than I remember.

Let’s start with how it’s worse. Novinha’s decision to lock Libo out of her data, the foundational decision in the story, makes no sense. I don’t want to get into details because I’ve already spoiled it enough but this Reddit post explains the issue if you’re curious. Nor is Novinha’s inexplicable decision the end of the contrivances. Card annoyingly employs several more to end up with the story he wants.

On the good side of things, if you decide to ignore the contrivances (which I mostly did) then it’s a powerful story, well written and full of great scenes. It’s a worthy successor to Ender’s Game, albeit very different stylistically.

In any case, now I’m finally ready to read Children of the Mind. I think the reason I haven’t read it previously is that I read Xenocide during that window when it had been released but Children of the Mind had not. Given the cliff-hanger ending of Xenocide I think if the next book had been out I would have made sure to read it. The fact that I didn’t leads me to believe that I couldn’t.

The Bullet That Missed (A Thursday Murder Club Mystery #3)

By: Richard Osman

Published: 2022

352 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

The further adventures of the Thursday Murder Club, a group of four English pensioners who solve old and new murders.

Who should read this book?

If you like Agatha Christie-style murder mysteries, this is the book for you. This third book has all the charms of the first two; if you liked them, I’m confident you’ll like this one as well.

General Thoughts

This was another thoroughly enjoyable entry in the series. As with most mystery novels, there are plot holes and people sometimes do things merely because that’s what the plot requires, but the same could be said for all modern media. (And nothing was as bad as Speaker for the Dead). As with most series, the implausibility continues to ratchet up. Also, Osman goes pretty easy on some of the bad guys, which contributes to the aforementioned implausibility. The four pensioners continue to be the strength of the series, though I think the longer the series goes the more it focuses on Elizabeth, the former MI5 agent. She’s set to be played by Helen Mirren in the forthcoming movie, so perhaps that’s understandable.

The Sandman: Book Two (The Sandman #2)

By: Neil Gaiman

Published: Original Comic book was 1990

560 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

The strange adventures of Dream/Morpheus/Sandman. This time with particular focus on his dealings with Hell and Lucifer.

Who should read this book?

I have long heard amazing things about this comic series. I was somewhat underwhelmed by the first collection, but the same can not be said for this collection. It was amazing. If this is your thing at all, you should read it.

General Thoughts

I’ve long thought that I need more comic books in my life, especially meaty graphic novels. This feeling was particularly acute after finishing this collection.

IV- Religious Reviews

The Pragmatist’s Guide to Crafting Religion: A Playbook for Sculpting Cultures That Overcome Demographic Collapse & Facilitate Long-Term Human Flourishing (The Pragmatist's Guide #5)

By: Simone H. Collins and Malcolm J. Collins

Published: 2023

483 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

Crafting religion and culture from scratch by borrowing the best parts of traditional religion and combining them with technological advancements (in particular technology which increases fertility.)

Who should read this book?

This book would be very useful for someone who’s not religious, but thinks religion is nevertheless beneficial. Though nearly the very first line of the book is “WARNING: This book will be wildly offensive to most people.” So there is that…

General Thoughts

I received a review copy of this book many months ago. I mentioned it at the time and bemoaned the fact that without the pressure to review it for the monthly round up I probably wouldn’t write down my thoughts and by the time it came out I would have forgotten some of my insights.

That is pretty much what happened, also this post is super long, and I’m tired, so I don’t have the energy to dig those insights out of the recesses of my memory.

One big thing that stuck with me was a metaphor. See, the authors want to create a religion from scratch, one that will solve the problems with the traditional religions, in particular the fact that none of them, not even the Mormons, seem to be able to keep their birth rate above replacement level. But for me, as a Mormon, this seems kind of silly, this is like deciding that rather than resurrect the broken-down car in the driveway, the one that was running pretty well up until a few months ago, that they’re better off 3D printing a car. This doesn’t make a lot of sense to me.

Of course, as a Mormon I’ve already got the hood up on the broken-down car, so I’m biased towards continuing to work on that. That said, I agree with their point about birth rates. Falling fertility is alarming. So much so that I’m going to be attending a pronatalism conference in December where they’re featured speakers. Perhaps while I’m there I can run my car metaphor past them and see what they think.

I guess we’re in a new phase where I’m supposed to urge you to like and subscribe. Well I can’t control your emotions, whether you like something is a very personal thing, but subscribing seems pretty straightforward.

Not sure if this is the right place to share these thoughts on The Network State... You'll tell me if it's not.

Balaji envisions new communities that start with a click of a mouse. And he is not wrong, this is an accurate description of the default 21st century community. But calling these social networks communities (little c) conflates them with the Communities (big C) of the previous 50 millennia or so. I suspect that this is a non-trivial mistake.

Click-based communities (*ccs*) of today are a built on exactly that - a click (click like, join, support, donate, etc.). Classic Communities (*CCs*) of the past were action-based, built on shared experience, and required hours, days and sometimes years of collaborative action in order to emerge. What does this mean? It means that *ccs* can have a lot of power as long as things are clickable. They can vote with a click. They can cancel with a click. They can join a movement with a click. They can buy/donate/fund with a click. They can announce a purpose with a series of 140 clicks. These are not trivial powers. And Balaji is very well versed in the technologies and dynamics of these communities.

But *ccs* are limited by the click options available. Outside of the click scope, these communities are entirely(nearly?) impotent. They can destroy, but they are rarely able to create. That's because according to the new rules, it is possible to destroy with a collective click. But creating is still defined by old rules, by man hours. *CCs* have always been very very different from *ccs* and followed the general socioeconomic rules of the IRL world. For something to happen, there needed to be ALPHA LEADERS and WORKER BEES. The ALPHA LEADERS, whether innovators or opportunists, would take actionable risks to set policy and give orders. The WORKER BEES took actionable risks to follow policy and follow orders. Even religion followed a similarly basic protocol. God says to love thy neighbor. Neighbor bakes apple pie and carries it across the street. The consistent variables in a *CC* were risk and work. Everybody took some kind of risk (smart or stupid) and everybody did work (the free riders were the outliers). In the *cc*, the risks are difficult to quantify because there is very little sacrifice of time and work required in a click. In fact, the *ccs* flipped the work pyramid in that a very few do the work (content creators) and the many do no work (default free ridership (powered by ads)).

Our new *cc* status quo came from a convergence of tech trends, economic trends, and an Information Age that made everybody much more informed. Today’s individual is much more likely to know that being a worker bee is a raw deal — "it’s not worth it"… and that being an alpha leader is also not such a great deal — it’s also not worth it. Ironically, or unfortunately, "it's not worth it" — a rational battlecry of this informed generation — is also a very powerful incapacitator. Human history is highlighted by people who took outsized (arguably irrational) risks, and worked into or lucked into outsize rewards — personal rewards, and more importantly, community rewards. The dumb parts —sacrifice, loyalty, work ethic - were sort of the best parts.

Back to Balaji. Balaji envisions a hybrid community of a *CC* and a *cc*. But I think Balaji has a bias. Balaji has spent the last several decades being surrounded by outliers. He was surrounded by studious outliers at Stanford. He was surrounded by entrepreneurial outliers at a16z. He was surrounded by creative outliers at Burning Man. He was surrounded by productivity outliers in the form of open source developers and new rules outliers in the form of crypto fanatics. He is no stranger to hard work, risk taking, sacrifice, commitment, etc. But this is not so for the minions, which is his blind spot.

For a community to start with one click is one thing, but to transition to the next stages, it needs to act in tens/hundreds/thousands of different ways. But the masses, being as disabled as they currently are, are unlikely to make that transition. At the individual level, it will simply not be worth it. Perhaps this is why we haven't seen Balaji's phenomenon (or a similar one) emerge in the recent years. *ccs* consistently start with a bang and end with a fizzle.

I guess there might be a hack for Balaji to dig himself out of this predicament. If a technology emerges that is robust enough to make clickability omnipotent... or at least potent enough to replace the old rules altogether. One can point to Dall-e 3 as a potential example, where powerful works of art and illustration, which previously required years of learning and hard work to accomplish, can now be done with several clicks. So I guess AI is the wild card. Great.

One issue I had with The Network State was Balaji's use of super-shitty examples of startup societies. They were like, "if all Zoolander fans start forming a society, and then start building models of schools, and then building other models at least twice the size..."

Also, what's Lavignia