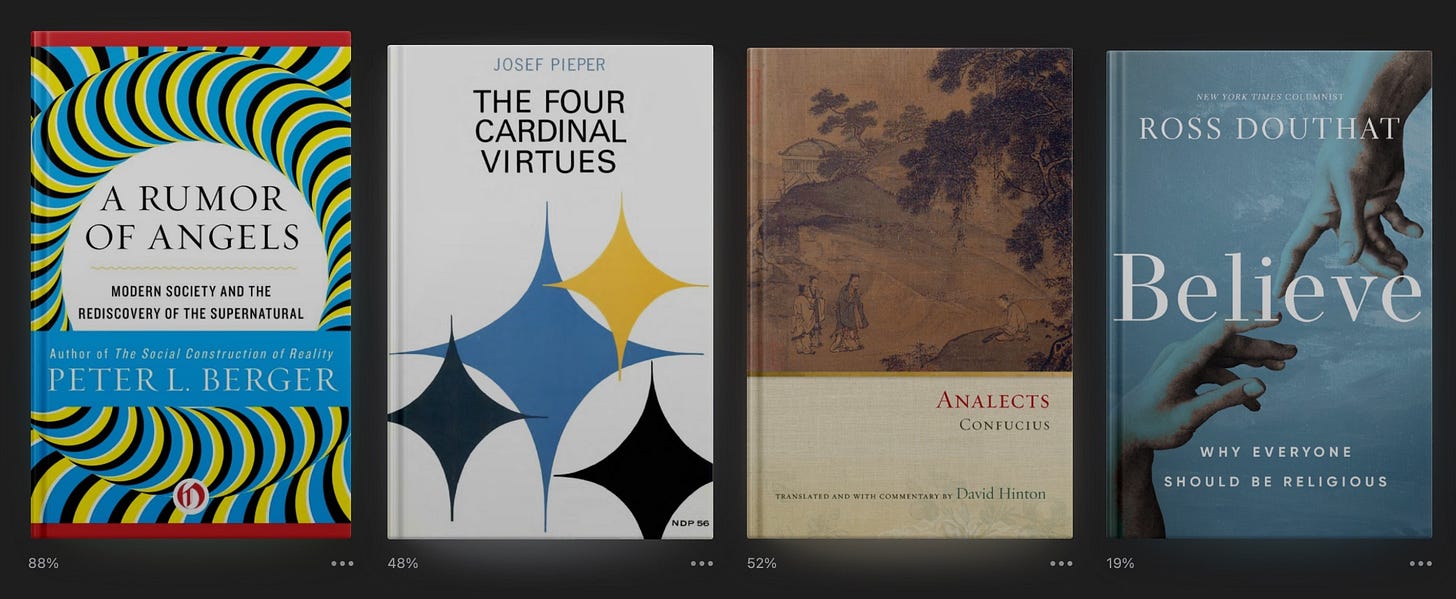

Reviews of (Mainstream) Religious Books: Volume 2

From the Analects of Confucius to Ross Douthat's exhortations to believe. And then two books from late 60's tossed in because why not?

A Rumor of Angels: Modern Society and the Rediscovery of the Supernatural

By: Peter L. Berger

Published: 1969

139 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

Reconciling religious belief and supernatural experiences to an increasingly secular world.

What's the author's angle?

Berger is more of a sociologist than an apologist. He’s definitely a defender of religion, but he approaches it from a social science perspective rather than a doctrinal perspective.

Who should read this book?

This book is kind of dated. In particular it brings in some postmodern ideas about the social construction of norms that feel out of character for someone defending religion. I would recommend Douthat’s Believe (see below) instead.

Specific thoughts: An early example of a secular defense of religion

If you imagine secularism as a mountain we’re crossing, then Berger’s book was written as we struggled up the lower slopes of the mountain. Now, many years later, we’re already over the peak and descending the other side. I don’t know that we’re very far past the peak, but we are a long way from the start, and we’ve learned a lot in the time since Berger wrote this book.

Much of his approach seems dated—not because he was necessarily wrong, but because we’ve now seen where things lead when untethered from Berger’s more cautious framing. He begins with the idea that truth is socially constructed (which was apparently the subject of an earlier book) and then uses this as a jumping off point for deeper reflection. He points out that if you think the New Testament is an example of socially constructed truth in a particular time and place, so is everything written in 1969. What’s good for the goose is good for the gander. I think these days, even people who appreciate this approach may nevertheless feel that any nods to social construction started us down a slippery slope that ultimately led to the epistemic chaos we’re currently experiencing. Still perhaps he’s correct, and the current approach is an unnecessary backlash. That the pendulum has swung too far.

It’s when he looks past things to try to get to a morality that persists regardless of social construction that things get more interesting, Nevertheless it’s hard to know how one draws a line. Or what line Berger might have drawn in 2025 as opposed to the line he drew in 1969, which struck me as being a little bit amorphous and arbitrary. To be clear this was deliberate on his part, but it turned out to be more slippery than sticky.

The Four Cardinal Virtues

By: Josef Pieper

Published: 1966

208 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

An examination of the four cardinal virtues of Catholicism: Prudence, Justice, Fortitude, and Temperance.

What's the author's angle?

Pieper was a German Catholic philosopher, who wanted to re-entrench these virtues. At the time he thought they had fallen out of favor. One wonders what he would think if he could see things today.

Who should read this book?

It’s pretty dense, as you might expect from religious philosophy. I think if you’re Catholic the reason for reading this book would be obvious. The more interesting question is what sort of benefit does it have for non-Catholics. As a Mormon I found it to be refreshing, and meaty.

Specific thoughts: Are we most lacking in fortitude?

As someone who didn’t realize Catholicism had four cardinal virtues until reading this book, I am not especially well positioned to offer commentary. Nor do I feel qualified to offer the Mormon exegesis of these virtues either. However, I do think I have a sense of how the average person in 2025 will react to something written in 1966, particularly something that’s stridently religious.

Of the four, one might imagine that the modern individual would have the most difficulty with temperance. A discussion of chastity makes up a significant portion of Pieper’s exhortations on temperance. Sexual liberation in all of its stripes runs into deep conflict with this virtue, and 2025 is well known for its liberal attitudes about sex. (Though I grant that such support is down from its peak). Despite this, I would argue that this is not the most difficult virtue for the modern man to accept. Most people may be very liberated when it comes to sex, but they’re still aware of the taboos and familiar with the opposing arguments. They may even possess a certain amount of sympathy on the margins for temperate attitudes, even if they reject most of the central claims.

Understanding this, I would argue that it’s actually the virtue of fortitude that presents the greatest challenge for the modern individual. Consider the quote from the book:

Thus, all fortitude has reference to death. All fortitude stands in the presence of death. Fortitude is basically readiness to die or, more accurately, readiness to fall, to die, in battle.

You can now see why a contemporary individual would have a more difficult time wrapping their mind around this than around exhortations towards chastity. I confess I’m having some difficulty myself imagining how a willingness to die in battle would manifest in someone’s daily life. Though it is clear that when Pieper talks about battle, he’s talking about a battle for the soul.

The essential and the highest achievement of fortitude is martyrdom, and readiness for martyrdom is the essential root of all Christian fortitude. Without this readiness there is no Christian fortitude.

An age that has obliterated from its world view the notion and the actual possibility of martyrdom must necessarily debase fortitude to the level of a swaggering gesture. One must not overlook, however, that this obliteration can be effected in various ways. Next to the timid opinion of the philistine that truth and goodness "prevail of themselves," without demanding any personal commitment…

Readiness to shed one's blood for Christ is imposed by the strictly binding law of God. "Man must be ready to let himself be killed rather than to deny Christ or to sin grievously." Readiness to die is therefore one of the foundations of Christian life.

On a fundamental, but also, hopefully, hypothetical level, I agree with this, but you can see where it’s not merely a difficult request, but a difficult thing to translate into normal daily living. Very, very few of us are going to be faced with the stark choice between death and denial. Though that may change, and it was not all that long ago, in the history of my own church, that such things took place, though even then they were exceedingly rare.

We will probably not be faced with the choice to deny our faith or be killed. But we are faced every day with the choice to endure. What must we endure? All manner of things: extreme pain, wasting illnesses, unexpected tragedies, and gross injustices. Patiently enduring all of these things also falls under the virtue of fortitude. And if there’s anything the modern world lacks even more than chastity, it’s patience and endurance.

Analects

By: Confucius

Published: The traditional date is 479 BC

160 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

Aphorisms from the Master (Confucius) and the basis for the civic religion of Confucianism.

What's the author's angle?

I’m obviously not qualified to offer up an opinion on the inner heart of someone writing thousands of years ago, but I would venture to assert that his primary value was stability.

Who should read this book?

Everyone. It’s short, it’s not hard to understand and it’s a classic.

Specific thoughts: The shallow vs. the deep

It would be the height of arrogance to assume that I could speak to the massive place of Confucianism in Chinese culture and history after reading a 160 page book. There’s obviously a depth to things that would involve many years of study before I was qualified to comment. So I’m only going to talk about the shallow.

I do think it’s possible to detect a certain Asian flavor to things when reading this book. I would describe this more as an awareness of the ways in which it departs from Western ideology than me having a definite sense of what it’s really about.

Despite having a better sense of what it’s not as opposed to what it is, one definitely is aware of encountering significant wisdom. But also things that are common to all cultures. Take this section for example which I opened to at random:

15. The Master said, ‘It was after my return from Wei to Lu that the music was put right, with the ya and the sung being assigned their proper places.’

16. The Master said, ‘To serve high officials when abroad, and my elders when at home, in arranging funerals not to dare to spare myself, and to be able to hold my drink- these are trifles that give me no trouble.’

17. While standing by a river, the Master said, ‘What passes away is, perhaps, like this. Day and night it never lets up.’

18. The Master said, ‘I have yet to meet the man who is as fond of virtue as he is of beauty in women.

15 sounds mysterious and exotic, but also important in some vague way. 16 represents the kind of stability, obedience to tradition and authority Confucianism is known for. 17 almost sounds like a repeat of what Heraclitus says about never stepping in the same river twice. And then 18 cracked me up. Because that just seems like a human universal.

As I often say about reading classics. They’re frequently far easier and more enjoyable to read than you think. I could certainly say that about the Analects.

Finally, I’ll leave you with my favorite aphorism:

The Master said, 'In the Book of Poetry are three hundred pieces, but the design of them all may be embraced in one sentence— "Having no depraved thoughts."'

Believe: Why Everyone Should Be Religious

By: Ross Douthat

Published: 2025

240 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

A case for religion both as a social good, and as a way of interacting with a world that still seems to possess a lot of inexplicable supernatural elements.

What's the author's angle?

Douthat is a well known NYT columnist and beyond that a noted believer. He certainly has a dog in this fight.

Who should read this book?

I really like Douthat, and I’m tempted to once again say, “Everyone”. But what I fear is that those who would take my recommendation will enjoy the book but not need it—while those who would benefit most are the ones likely to ignore it.

Specific thoughts: Can anyone be swayed on anything?

This book has received quite a bit of coverage and been reviewed already in lots of outlets with far bigger readership than my humble blog. (If you want a short, but somewhat snarky review see this one in The Economist. For a long, very detailed review consider Mr. and Mrs. Psmith’s excellent review.) Given that it’s been reviewed better elsewhere, and also that I’m horribly behind on my book reviews, I don’t intend to spend much time on it.

I will say that I quite enjoyed the book and felt like, had the course of my life been different, it’s a book I might have written. So, it’s fair to say that I’m not a neutral observer, and, unsurprisingly, I found all of Douthat’s arguments to be very compelling.

On the other side of things you don’t have to dig much on Amazon or Goodreads to find reviews calling Douthat out for sloppy reasoning, tendentious arguments, and defending absurdities. So the question I was left with: is there anyone in the middle these days? Is there someone who reads this book and reacts neither by vigorously nodding along, nor with undisguised venom? I hope so, and if there is, then those are the people who should read this book.

As I persist in mentioning, so much so that it’s almost certainly becoming tiresome. I’m behind on all my writing projects. I’m spending the last half of June in Iceland, so this situation will almost certainly get worse before it gets any better, but I am hoping to push a few more things out before I leave, but no promises. Mostly I just want to thank everyone for their ongoing support and patience.