Origins of Efficiency - The Glories of the Modern World

We have a lot of nice things. We’re really good at making nice things. We should preserve these nice things. But also nothing lasts forever?

By: Brian Potter

Published: 2025

384 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

The clever and incremental ways we’ve vastly increased humanity’s ability to make stuff. We’re constantly finding ways to build stuff cheaper, faster, and with fewer resources.

What’s the author’s angle?

Potter is probably best known for his Substack Construction Physics, which covers infrastructure, manufacturing, and building stuff in general. He also works at the Institute for Progress. Put those two together and you’ve got someone who’s a big fan of material progress, or what is sometimes referred to as a techno-optimist.

Who should read this book?

If you want some amazing stories of how processes have improved, and a stirring defense of the modern world and all its wonders this is a great book. If you’re looking for higher level reflection on what it all means, particularly any sort of caution around progress and efficiency, then this is not the book for you. Potter is definitely an “onward and upward!” kind of guy. He does note that efficiency can’t be applied everywhere, and that it’s often constrained by other goals, like safety, but he still treats it as being inherently good.

What does the book have to say about the future?

The book does point out that efficiency has become a “sociotechnical” issue. Particularly in the West, we often make choices to constrain efficiency as part of some broader societal goal. Potter doesn’t talk very much about China, but one could imagine that their drive for efficiency is not constrained in the same way and, going forward, this could give them the edge in our ongoing competition.

Specific thoughts: Fantastic, awesome, hopeful, and scary

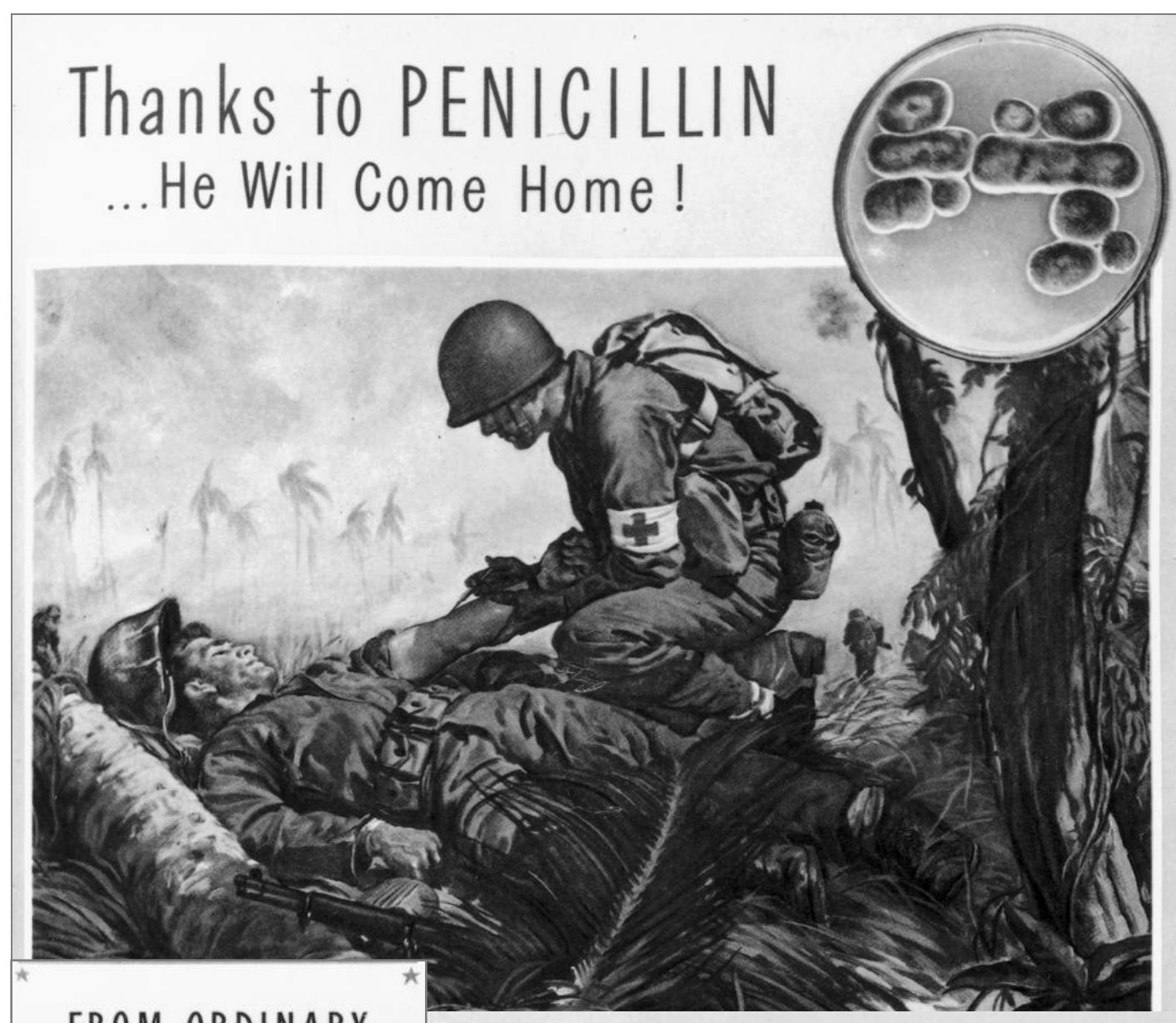

Potter introduces his subject with the story of penicillin. We all know about Fleming’s serendipitous discovery of penicillin, which occurred in 1928, but most people don’t know much beyond that. Everyone (including myself) assumes that penicillin gets discovered. We start giving it to people. Bacterial infections are finally treatable. Victory! But that’s not how it went at all. Fleming discovered penicillin in 1928, but it wasn’t until 1939 that Florey, Chain, and Heatley were able to isolate it. That may seem like the end of it, but it was really only the beginning. Producing it in sufficient quantities to do anything with it was still devilishly difficult. As Potter explains:

In actuality, Penicillium notatum, the species of fungus the scientists used to produce penicillin, only generated the substance in miniscule amounts. In fact, over the course of an entire year, the researchers had gathered such a small amount of penicillin that they exhausted their supply during the initial trial, and the police officer they had treated relapsed and died. Yes, penicillin was a miracle drug—but without a way to produce it in large quantities, it was of little use.

We can debate which of the many required steps of the journey was the most difficult: the initial discovery, the isolation, or figuring out how to mass produce it? But there’s a strong case to be made for that last step. I’m not going to detail every innovation and invention, but there were several, from locating a more suitable growth medium for the mold, to finding a strain that was better at producing penicillin, to selective breeding of that mold.

There was a lot of time pressure because as all of this was going on World War II had started, and there was a desperate need for an antibacterial agent. The scientists responded to this pressure with flying colors:

The overall increase in the volume of penicillin produced through these improvements was staggering. According to Emory School of Medicine professor Robert Gaynes, “In 1941, the United States did not have sufficient stock of penicillin to treat a single patient. At the end of 1942, enough penicillin was available to treat fewer than 100 patients. By September 1943, however, the stock was sufficient to satisfy the demands of the Allied Armed Forces.”

Penicillin production reached 80 million units per month in 1943. By early 1944, it had risen by a factor of 200 to over 18 billion units per month. By 1945, manufacturers around the world were producing 5 tons of penicillin annually. And as production volumes rose, the price of penicillin fell. In 1943, a 600-milligram vial of penicillin cost $200; by 1952, the same vial cost just $1.30.

The book is full of similar stories. For example:

1- Nails: In the beginning nails were hand-forged. A blacksmith working full time might be able to make a few thousand per day. In the late 1700s we started to get cut-nails, and early machines could do around 10k/day. Once steam power came along that went to around 30k/day. Further improvements have given us a machine that can do around 100k/day.

2- Incandescent bulbs: In the beginning light bulbs were blown by hand. Over the decades there was a similar increase in efficiency, until eventually we reached the ribbon machine:

The ribbon machine represented the final evolution of incandescent bulb blank production. It produced bulbs in such enormous quantities that by the early 1980s, fewer than 15 ribbon machines were needed for the entire world’s supply of light bulbs. By then, machine improvements had increased the production volume to nearly 120,000 bulbs an hour, or 33 bulbs every second.

3- Ford’s assembly line: The first attempt at an assembly line cut production from 12.5 hours to 6. Within a few years, by April 1914, a Model T could be assembled in 93 minutes.

4- Photovoltaic solar panels: “The cost per watt of solar PV panels has fallen precipitously in the past four decades, from $100 in 1975 to just $0.26 in 2021 in inflation-adjusted dollars.”

Reading these stories filled me with two competing emotions:

On the one hand I was filled with my own brand of techno-optimism. How could I not be? As I read example after example of the amazing things technology had accomplished—encountered wonder after wonder, and miracle upon miracle—I had no choice but to completely embrace the gospel of progress and the light of efficiency. Sure, one is naturally nostalgic for ancient methods of living, but once you’re confronted by the idea of blowing light bulbs by hand, or hammering out nails one at a time, that nostalgia disappears pretty quickly.

On the other hand, it also fills me with terror. This latter emotion does not flow as obviously from the text as the previous one, but it may be the more important of the two. I hear about all of these amazing efficiencies, and marvelous processes, and I wonder what happens if things start going poorly. To explain all this it might help to back up a bit. There’s lots of debate over what exactly it meant for the Roman Empire to “fall”. There are arguments that the decline wasn’t that severe; or that common people were better off; or that as long as Constantinople stood, “Rome” had not really fallen. But let’s set those issues aside for the moment and talk about pottery.

Whatever else may be said about the decline of Rome in the 5th century, the archaeological record is clear: high-quality wheel-thrown pottery—made in a central location and exported long distances—disappears. And in Britain, wheel-thrown pottery, of any sort, basically disappears entirely.

I’m drawing from the book The Fall of Rome by Bryan Ward-Perkins. In the Roman Empire pottery was the thing they got very efficient at, and might act as a good analogy for our own areas of efficiency. Here’s what Ward-Perkins had to say about it.

Three features of Roman pottery are remarkable, and not to be found again for many centuries in the West: its excellent quality and considerable standardization; the massive quantities in which it was produced; and its widespread diffusion, not only geographically (sometimes being transported over many hundreds of miles), but also socially (so that it reached, not just the rich, but also the poor). In the areas of the Roman world that I know best, central and northern Italy, after the end of the Roman world, this level of sophistication is not seen again until perhaps the fourteenth century, some 800 years later.

Can we use Roman pottery to help us understand our own potential decline? If so, how would we go about that? I can think of several ways things might go. Let’s go from least apocalyptic to most apocalyptic:

Of course there’s always a chance that the US won’t enter a period of decline. Unlike every other great nation the US will endure forever, because? … something … something … AI?

Perhaps the US will enter a period of decline, but some other nation will pick up the torch. We won’t be able to produce our own equivalent of “advanced pottery”, but someone else will, and we’ll be able to get it from them. Sad, but not catastrophic, and arguably already happening.

Maybe we’ll lose the bleeding edge of technology and efficiency. Perhaps centralized pottery manufacturing in the 400s maps to gigantic, power-hungry, AI data centers, in the 2020s. And if there is a decline we’ll lose something like that, but we won’t lose car manufacturing, or the internet, or transoceanic shipping.

Or maybe, we should imagine something far worse. I mean, throwing pottery on a wheel, with the associated firing and glazing, is not all that high tech. But it nevertheless disappeared entirely in Britain. Elsewhere the quality markedly declined as centralization and standardization went away. It appears that this wasn’t so much knowledge disappearing, but rather a collapse in demand. People had more important things to worry about than getting really high quality pottery. Especially when crude pottery does 90% of the job.

At this point long-time readers might expect me to start harping on fragility, and that’s definitely in there, but the disappearance of pottery wasn’t a matter of the system breaking (however delicious pursuing that pun might be) it was a matter of slow erosion of capabilities like shipping routes, and centralization, combined with a cratering of demand. To place it in our own times, what does the high-end GPU market look like if we were to suffer something similar to the Great Depression, while simultaneously shipping becomes 10% harder because of simmering geopolitics? Frankly I don’t know, but as the pandemic-era supply chain chaos illustrated, it doesn’t take much for efficiencies to turn into fragilities. And however cool our systems are, if no one wants what they’re producing then they will decay and eventually disappear.

—------------------------------------------------------------------------

I can never decide if it’s completely silly to compare the world of today to the Roman Empire, or if it provides some kind of deep lesson that we ignore at our peril. That said, I couldn’t resist comparing our efficient production to their efficient production. I expect that I will continue to draw tenuous connections between all manner of things. If tenuity doesn’t bother you, or better yet if you actually appreciate it, consider subscribing.

I use penicillin as an example of both capitalism and the power of government with my econ students.

I forget the exact numbers on the slide, so these are estimates:

1940 -- essentially priceless

1942 -- $175 / dose

1943 -- $20 / dose

1945 -- 50c / dose

1950 -- 3c / dose

I love Potter's substack, so this sounds like a great book.