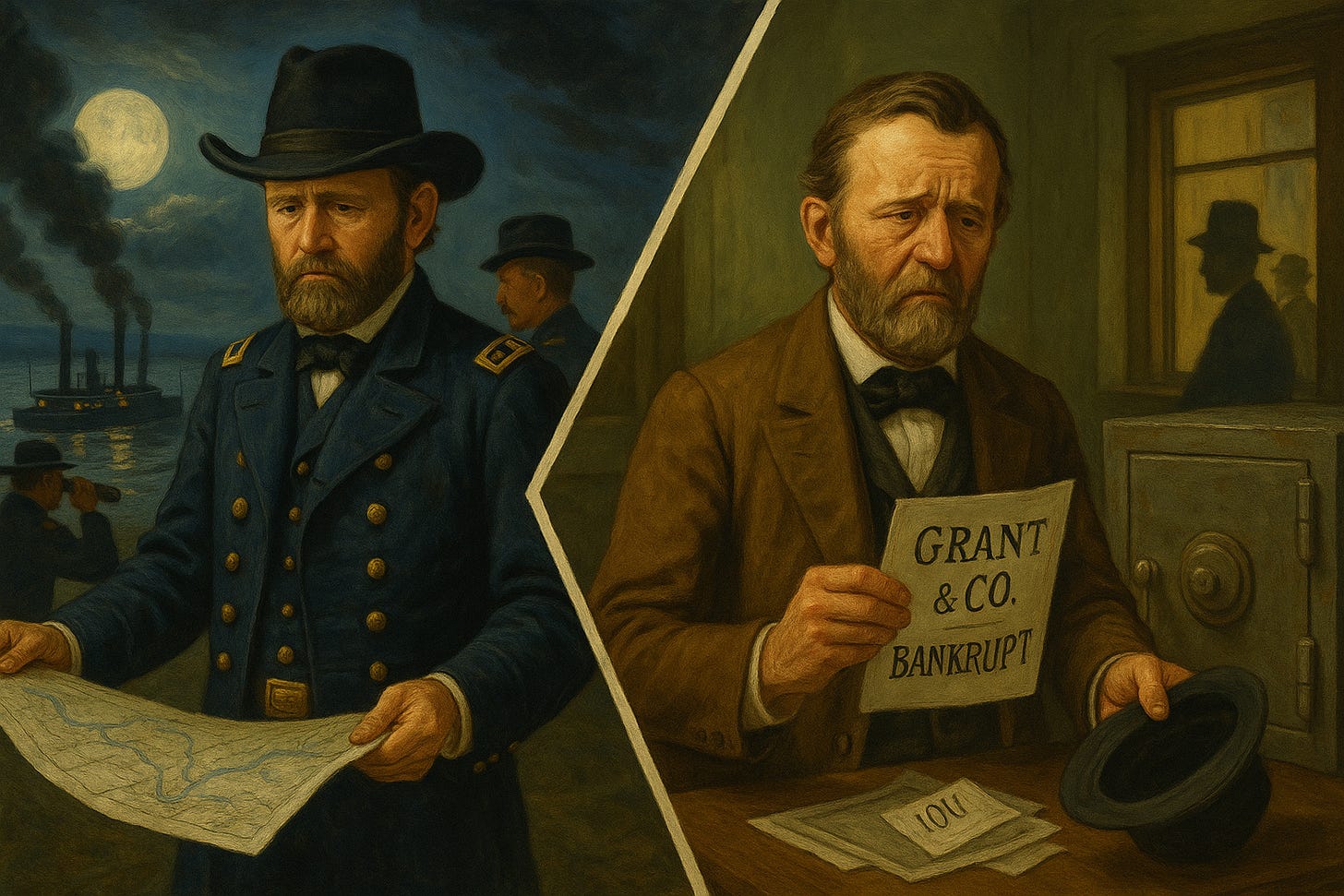

Grant - A Brilliant General Constantly Deceived by His “Friends”

A man who possessed a singular talent for making war and being duped.

By: Ron Chernow

Published: 2017

1104 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

A biography of Ulysses S. Grant, the greatest general of the Civil War, but also simultaneously one of the most guileless individuals ever profiled by a biographer.

What’s the author’s angle?

Chernow clearly thinks that Grant has been unfairly maligned as a corrupt drunkard, and this book is going to set the record straight. In Chernow’s telling, Grant was the best general of the war, one of the better presidents, and overall a very honorable man whose only fault was that he was far, far too trusting. I’m not saying that Chernow is wrong about any of this, merely that there is a touch of the hagiographic to this book.

Who should read this book?

I’ve thoroughly enjoyed every Chernow book I’ve ever read. They’re long, but they go down pretty easy. (Though reading about the brutality of reconstruction—i.e. the original Klu Klux Klan and its offshoots was extremely sad and painful.)

Specific thoughts: How can someone be so good at fighting enemies on the battlefield and so bad at detecting treachery in those closest to him?

The central mystery of the book is reconciling Grant’s reputation as a general with his absolute gullibility in every other aspect of his life. Put another way, how could he be so absolutely resolute and steadfast when it came to war, and such a pushover everywhere else? Let me provide a couple of examples from early in his life to illustrate what I mean:

In Sackets Harbor, he and Julia had befriended a prominent family, the Camps, who were ruined by a railway investment. To rescue Elijah Camp, Grant paid for him to accompany the regiment to Columbia Barracks, where Camp opened a sutler’s store and Grant, with pay saved up from the Panama journey, supplied the needed $1,500 in capital. The con artist and the scoundrel always found a ready target in U. S. Grant. While the business boomed, Camp balked when Grant asked for a profit statement and “began to groan and whine and say there was no money in his trade at all,” Julia said. Perhaps detecting Grant’s gullibility, Camp complained that he would feel better owning the business outright. Grant, always good-natured to a fault, agreed to withdraw his $1,500, apparently taking $700 in cash and $800 in personal notes from Camp. “I was very foolish for taking it,” Grant admitted to Julia, “because my share of the profits would not have been less than three thousand per year. Still not satisfied, Camp began to assert he couldn’t sleep at night, worrying that the notes Grant held might fall into the wrong hands. The obliging Grant then burned the notes by candlelight in front of Camp. Camp sold gunpowder in the shop, and when some of it accidentally blew up the store, he decided to return to Sackets Harbor. He refused to pay Grant the $800 he owed him, even though he had earned ten times that amount.

That’s a long quote, but it’s necessary because each sentence contains some new, ridiculous mistake made by Grant. How was this man, who was comprehensively out-manuvered by one scoundrel, the same man who outmaneuvered every army he encountered during the war? Let’s consider one more example:

Short of funds, [Grant] went to his friend Captain Thomas H. Stevens Jr., an officer who had begun a banking business. Grant had left $1,750 with Stevens in January and expected to collect that amount. Stevens offered 2 percent monthly interest and a more sophisticated investor might have realized no legitimate banker paid such exorbitant rates. “I can’t pay you now,” Stevens insisted, “but if you will wait a couple of weeks I will pay you in time for you to take the next steamer.” The obliging Grant agreed. Julia narrated the sequel: “At the end of the two weeks, the captain returned to find that Stevens had conveniently gone out of town and the captain was again cheated.” Once more the credulous Grant had been duped by a trickster in what had become a striking pattern. Clearly other people thought him something of a simpleton who could be defrauded with impunity. Not until 1863, amid the Civil War, did Julia send Stevens a blunt letter and finally receive belated payment.

It would be one thing if Grant grew out of this gullibility. It might be understandable that he was too trusting in 1854, but certainly by the end of the war, or the start of his presidency, or at least by end of his presidency, he had learned to be more cautious. However this was not the case. Grant’s credulity was a permanent feature till the end of his days.

The previous quote mentioned that a sophisticated investor would have realized that 2% a month was an exorbitant rate of interest. One would hope that Grant would have internalized that lesson and been skeptical of such claims going forward, instead he ended up falling for an even more outrageous scheme decades later when he was 58. This scheme was far more elaborate, and had the trappings of Wall Street, but the projected profits were even more outrageous. In this case Grant was targeted by Ferdinand Ward, a “pathological narcissist” who had “the psychopath’s ability to counterfeit sincerity”.

Ward sized up Grant as a “child in business matters” who would never be able to uncover his deceptions. The firm paid Grant $2,000 monthly for living expenses and Ward funneled extra money to him as needed. Grant associates who invested with Ward walked away with dazzling profits. One friend invested $50,000, disappeared for six months on a European vacation, then came home to a whopping $250,000 check. As others reaped 15 percent to 20 percent profits per month, a mania to invest with Grant & Ward overtook Wall Street. The stupendous returns dulled investor curiosity about how these exorbitant returns were earned and dozens of Union veterans poured in money on the strength of Grant’s name alone.

As you have certainly guessed it was a Ponzi scheme, which collapsed in spectacular fashion. And Grant not only put all of his own money into it. He convinced everyone he knew to put their money into it as well, so that his entire extended family could be ruined when it collapsed. (To say nothing of the Union veterans mentioned in the quote.) When the smoke cleared, one person estimated that Grant only had $18 to his name. And though he didn’t know it at the time, he only had about a year to live. Fortunately he was convinced to write his memoirs. Even more fortunately, Mark Twain was able to keep him from being taken advantage of one last time. As a result, he was able to leave his widow a significant sum of money as basically his final act.

I’m not trying to make you think less of Grant. Nor am I disputing Chernow’s assessment of Grant’s generalship. I’m just genuinely mystified that the person who was duped over and over again by every “con artist and scoundrel” he encountered, could also be the greatest general of the Civil War.

One is tempted to imagine that his gullibility was somehow a necessary component of his generalship, but I see no evidence of that. I see no evidence that it helped him out at all. You might think that it made people more loyal, but that doesn’t appear to have been the case. Generally people didn’t like him at first and only grew to appreciate him once they saw him in action. Also he suffered all manner of disloyalty as well. One of the great scandals of his administration was perpetrated by his personal secretary, a man who had been with him since the Siege of Vicksburg.

All of these stories of being duped make for a fascinating, but sometimes frustrating, read. Still, I suppose someone reading my biography would come to similar conclusions. The fact that he rose above all these reversals and managed to achieve the success he did, should be inspiring to us all. May we all have a little bit of Ulysses S. Grant in us.

Grant’s reputation was sky high when he died, despite the Ponzi scheme. It was mostly the Lost Cause narrative that threw him into disrepute. My wife often tells me that this blog is a “Lost Cause”. I don’t know that there’s any connection between the two, though both are disreputable and frequently wrong. Still some people find the latter to be enjoyable at least. If you’re one of those people, consider subscribing.

There was an interesting comment on Grant in Battle Cry of Freedom that I think bears on this. It said that Grant as a general was never very concerned about what the enemy was about to do to him, and was instead focused on his plan to attack the enemy. This mostly worked because of the war he fought, modulo a couple battles where the other side acted first. And like his gullibility, this never seemed to go away. I could easily see the two being connected.

For a paltry $1000 up front, I can promise you myriad subscriptions mere years hence.