A Short History of England - What Gives a Country Its Soul?

Chesterton mostly lost me after Arthur and Alfred, but I feel like I got his point in spite of that.

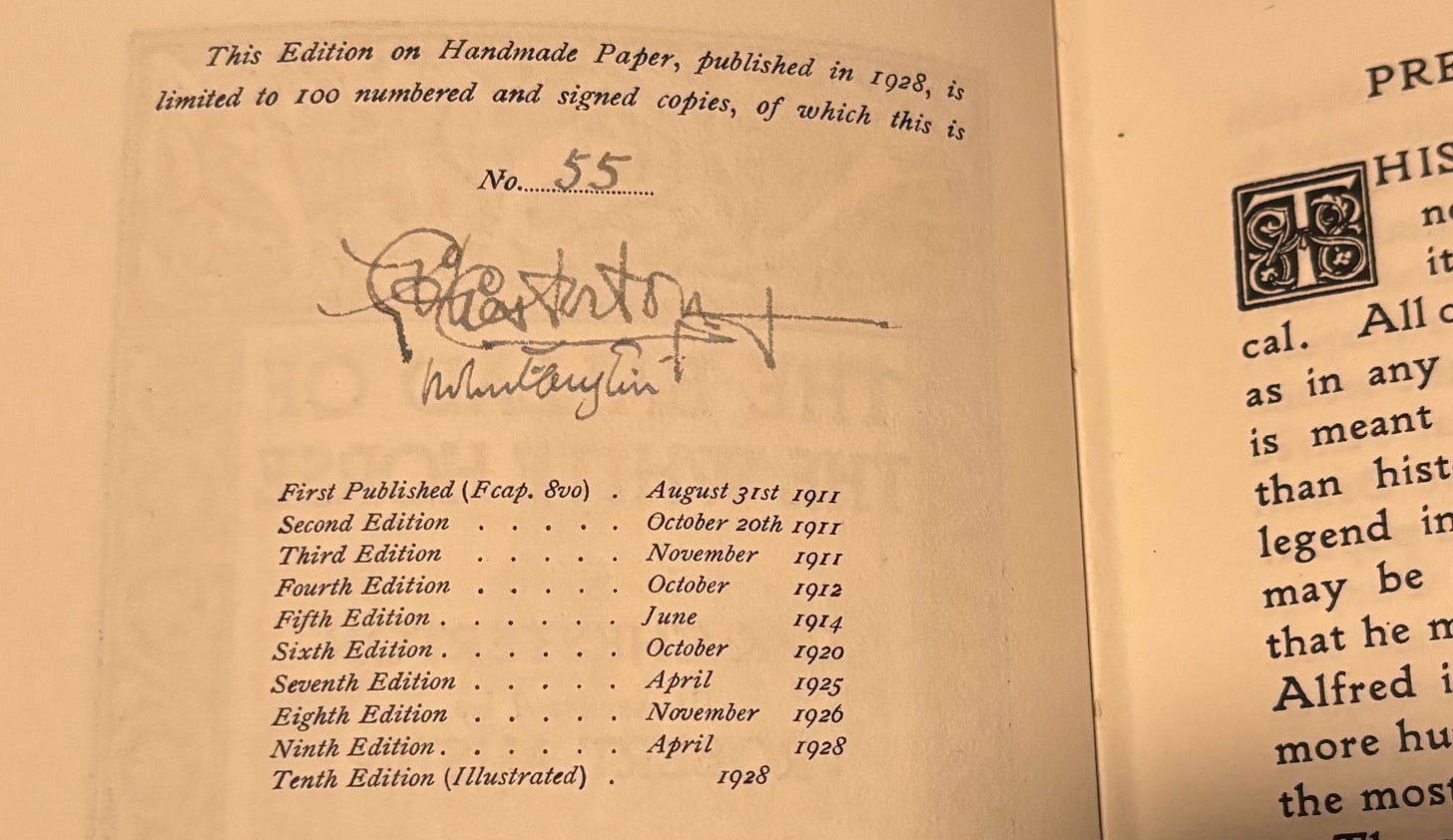

By: G.K. Chesterton

Published: 1917

107 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

The book is titled the “History of England”, but it’s really a book about the soul of England. Chesterton examines this soul chronologically from the “Age of Legends” down to the time the book was written, which happened to be the middle of World War I.

What’s the author’s angle?

It’s Chesterton, so there’s obviously a religious angle, and a traditional cultural angle. Even expecting this, I was surprised by how much he missed the old guild system, and other features of medieval life. There’s a lot of anti-rich sentiment in the book, but he’s also no socialist either.

Who should read this book?

I don’t think it’s practical or even wise to read everything Chesterton wrote, but I have a vague goal to read most of what he’s written. Even then I’m pretty sure that knowing then what I know now I would have advised myself to skip this book, or at least only read the first few chapters.

The big problem is that Chesterton is not dispensing English history (contra the title) he’s interpreting it. He assumes you already know a ton of history, and he’s just going to tie it together in a new way. I’m sure a highly educated Englishman in 1917 would have had no problem with Chesterton’s references, but 100 years on, this poor American was frequently completely lost. Here’s an example:

It will be apparent, when I deal with that period, that I do not palliate the real unreason in divine right as Filmer and some of the pedantic cavaliers construed it. They professed the impossible ideal of “non-resistance” to any national and legitimate power; though I cannot see that even that was so servile and superstitious as the more modern ideal of “non-resistance” even to a foreign and lawless power. But the seventeenth century was an age of sects, that is of fads; and the Filmerites made a fad of divine right.

Who or what is Filmer and the Filmerites? One could look it up (apparently it refers to a 17th century political theorist, Robert Filmer) but you’re not going to get any information from the book. This selection, with its two references, is the first and last time the name shows up.

I’ll tell you what I got out of the book and you can go from there, but as a general matter I wouldn’t recommend reading this book. It has all the normal Chesterton witticisms and turns of phrase, but there are easier places to get those.

What does the book have to say about the future?

I’ve long been interested in civic religion, what might be called the soul of a nation, and it’s clear that the soul of America (and other western countries) is fracturing. Chesterton saw a similar fracture in England during WWI. Despite this the country came together under Churchill in WWII and acquitted itself rather well given its declining powers. (Did Churchill give voice to the soul of the nation, or did he shape it in some respect?)

Is the fracturing of our own national souls a matter of no import? Is the national soul something that deserves to be washed away by globalism or the singularity? Or is its health the critical issue of our time?

Specific thoughts: The health of modern England may depend more on the public’s reverence for King Arthur than on their opinion of Keir Starmer.

Early in the book Chesterton speaks of King Arthur. (Fortunately, unlike Robert Filmer, I know something about Arthur.) Chesterton speaks of the place of Arthur in the English soul:

But the paradox remains that Arthur is more real than Alfred. For the age is the age of legends. Towards these legends most men adopt by instinct a sane attitude; and, of the two, credulity is certainly much more sane than incredulity. It does not much matter whether most of the stories are true; and (as in such cases as Bacon and Shakespeare) to realize that the question does not matter is the first step towards answering it correctly. But before the reader dismisses anything like an attempt to tell the earlier history of the country by its legends, he will do well to keep two principles in mind, both of them tending to correct the crude and very thoughtless scepticism which has made this part of the story so sterile. The nineteenth-century historians went on the curious principle of dismissing all people of whom tales are told, and concentrating upon people of whom nothing is told. Thus, Arthur is made utterly impersonal because all legends are lies, but somebody of the type of Hengist is made quite an important personality, merely because nobody thought him important enough to lie about. Now this is to reverse all common sense.

Obviously the “scepticism” exercised by “nineteenth-century historians” was part of an admirable quest to establish facts. And we all agree that facts are important. To place it in the context of our own myths there’s the one about George Washington chopping down the cherry tree. Supposedly he was asked about it and responded that he “could not tell a lie”, he had chopped it down. It’s definitely a worthwhile endeavor to establish that the story was made up by one of Washington’s biographers, rather than something that actually happened. But what effect does this stripping away of legends mentioned by Chesterton have on the nation’s soul/civic religion?

Debunking one legend/myth, like the cherry tree, doesn’t appear to be a very big deal. And may in fact be a positive thing, but Chesterton asks what happens when we chop away (pun intended) all the legends and myths. As he points out:

We may find men wrong in what they thought they were, but we cannot find them wrong in what they thought they thought. It is therefore very practical to put in a few words, if possible, something of what a man of these islands in the Dark Ages would have said about his ancestors and his inheritance. I will attempt here to put some of the simpler things in their order of importance as he would have seen them; and if we are to understand our fathers who first made this country anything like itself, it is most important that we should remember that if this was not their real past, it was their real memory.

What’s more important: a nation’s “real past”, or its “real memory”? Educated people are inclined to say that the “real past” is more important, but recently quite a bit of energy has been devoted to people’s “real memory”. On the one side some people have a “real memory” that the 2020 election was stolen. On the other side people have a “real memory” that Michael Brown had his hands up when Darren Wilson shot him. Does this mean that we need to put even more emphasis on the “real past”? I don’t think so. I think Chesterton is making a very important point. The “real memories” of England formed its civic religion. King Arthur might not be the real past, but the “memory” of his deeds, and his ideals were its real soul.

Rightly or wrongly, [the Arthurian] romance established Britain for after centuries as a country with a chivalrous past. Britain had been a mirror of universal knighthood. This fact, or fancy, is of colossal import in all ensuing affairs, especially the affairs of barbarians.

When we banish these ideals and treat them as fables we don’t end up with a rational, fact based view of history. We end up with other “real memories” filling in the space. A soul that’s fractured and contentious. A variety of civic religions that aren’t based on the majesty of Arthur and his knights or Washington and his cherry tree. Rather we end up with sects defined by grievances and anger, built around “memories” of the wrongs which have been committed against us, rather than the virtues which unite us.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

As I finish this review I wonder if I need to take a different approach to reading Chesterton than the one I’ve been pursuing. There is a sort of haphazardness to my reading and my writing. The new year approaches, maybe some kind of resolution can fix it. Probably not. Much like Chesterton, I’m a man of strong and outdated opinions, not to mention calcified habits. I think haphazardness is baked into the system at this point. If you don’t mind that, consider subscribing, if you do mind it, I wonder how you get by. The world is a very haphazard place.

I think the only Chesterton I've read was The Ballad of the White Horse, after the glowing recommendation in ACX's book review contest. I faced a similar problem here, of less historical grounding of the history of that Isle to interpret the references, and faced the further veil of, if not archaic, at least a bit distant poetry. But on the other hand, the language itself was at times rewarding, and I had the pleasure of putting my daughter to sleep with it as I read aloud.

Amusingly King Arthur (if he existed) was not only not English, but an enemy of the English!